| |

Fall 2001 / Winter 2002

Fall 2001 / Winter 2002

Volume 21, Number 4 and Volume 22, Number

1

|

Sentient beings are interrelated in every way. We live in the same world,

breathe the same air, eat and drink together, live and die together. Why,

then, do we find it so difficult to experience compassion for each other,

for all sentient beings?

Chan Master Sheng-yen

|

Chan Magazine is published quarterly by the Institute of

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Culture, Chan

Meditation Center, 90-56 Corona Avenue, Elmhurst, New York

11373. The Magazine is a non-profit

venture and is supported solely by contributions from members of the Chan Center and the

readership. Donations to support the Magazine and other Chan Center

activities may be sent to the

above address and will be gratefully appreciated. Your donation is tax deductible.

For information about Chan Center activities

please call (718)592-6593.

For Dharma Drum Publications please call

(718)592-0915.

Email the Center at ddmbaus@yahoo.com,

or the Magazine at chanmagazine@yahoo.com,

or visit us online at http://www.chancenter.org/

©Chan Meditation Center

Founder/Teacher: Shi-fu (Master) Ven. Dr. Sheng-yen

Managing Editor: David Berman

Contributing Editors: Ernie Heau, Linda Peer, Chris

Marano, Virginia Tan, Buffe Laffey, Rebecca Li, Charlotte

Mansfield, Stacey Polacco, David Slaymaker, Wei Tan, William Wright,

Guo Zhen, Cari Luna

Co-ordinator: Virginia Tan

Design and Production: Jui Jung Lin, Tasha Chuang,

Linda Peer

Cover Design: Chih Ching Lee

A Word from the Editor

Impermanence

Everything changes; nothing stays the same. People move, change jobs,

get married, have babies, go back to school, get sick, or

suddenly, unexpectedly die.

On September 11th, we were all reminded, in the most sudden and terrible

way, of the undeniable, inescapable truth of impermanence.

Here at Chan Magazine we've experienced a flurry of changes in the

last year or so -- none of them, thankfully, related to the events of

9/11 -- and some of them have had an impact on our ability to get the magazine

to you. We 're aware that the last few issues have been late,

and we're aware that they haven't always received our best attention.

So, beginning with this issue, we're vowing to take the best advantage

we can of the opportunity that is constantly being presented by the inevitability of change.

You 'll notice that this is a double issue -- that 's to help us get back on

schedule, and to give us an opportunity to replace some valuable staff

who have had to move on.

You may also notice some other changes -- they 're just a

beginning, and we 'd like to engage you, our readers, in the process of making

Chan Magazine more useful to you.

If you have any suggestions, any contributions, stories,

poetry, photography, artwork, or ideas about how you can be of service to the magazine,

or how the magazine can be of better service to you, please send them to the address on

the back cover, or better yet, email them to us at chanmagazine@yahoo.com.

We look forward to hearing from you, as we enter the entirely

new, always unpredictable future.

Thank you, in the Dharma,

The Editor

A Note about Romanization

Spelling Chinese words with the Western alphabet has always been a problem; there

are at least a half-dozen systems in use today. The Pinyin system was adopted by the

People's Republic of China as its official system in 1958, but with so many scholars,

journalists, business people, politicians and Chinese expatriates using other systems,

it has been slow to catch on. The U.N. made it their official system in 1977, and

since then, Western users of Chinese vocabulary have gradually followed suit.

We began making Pinyin our standard with the Fall 1999 issue, when "Ch'an"

became "Chan" in the name of the magazine,but it hasn't been possible to be

entirely consistent. Names, for example, go on licenses, and contracts, and copyrights, and their spelling can't be changed to meet an arbitrary standard. (Our

spiritual leader, Chan Master Sheng-yen, is known worldwide by that name, so it

retains the hyphen, which in Pinyin would be dropped.)

The important thing is that we'd like our readers to know what we're talking about,

so we're going to do our best to alleviate confusion by rendering Chinese words

in Pinyin. Ancient names and Buddhist technical terms will be in Pinyin ("Tao"

becomes "Dao", "Ts'ao Tung" becomes "Caodong",

"Lin-chi" becomes "Linji".)

Modern proper nouns and titles will be left as they are, and as for living persons,

everyone retains final approval over the spelling of their own names.

The Editor

Song of Mind of

Niu Tou Fa Rung

Commentary by Master Sheng-yen

This article is the

thirty-fourth from a series of lectures given during retreats

at the Chan Meditation Center in Elmhurst, New York. These talks

were given on June 1,1988,and were edited by Chris Marano.

All Buddhas of the past,

present and future,

All ride on this basic principle.

The "principle" the song speaks of refers to what the previous verses say: that once you become enlightened, or are "inside enlightenment," then you no longer feel that there is an enlightenment to attain. All vexations and all attachments are gone. That is not to say, however, that nothing exists. True emptiness is true existence, but only if you can experience true emptiness will you know what true existence is. Buddhas are Buddhas because they "ride," or are in accordance with, this principle.

When sutras and other Buddhist texts speak of "all the Buddhas of the past, present and future," it seems as if they are talking about entities other than ourselves, entities who have nothing to do with us. Actually we are included in this group and represent the Buddhas of the future. Sakyamuni, Amitabha, and several other Buddhas mentioned in liturgies are Buddhas of the present. In fact, there are innumerable Buddhas of the present presiding over innumerable worlds. If they were Buddhas of the past, we would know nothing about them. Sakyamuni is a Buddha who resides in this world and time and whose teachings still touch us. Sutras say that in this kalpa (an unimaginably long period of time), there will be thousands of Buddhas who appear, and that Sakyamuni was the third in this long list. According to the sutras, Maitreya will be the next Buddha to appear; somewhere and sometime in the remote future, all of us will also be Buddhas.

If you wish to visit Buddhas of other worlds and times, then I suggest you start saving up for that journey

now, because it is a long and costly trip. On the other hand, there really is no need to go

anywhere. We are already blessed because Sakyamuni is right here and right now in our

world. If you are going to plan for anything, let it be for your own

Buddhahood, even if it is a hundred trillion years from now.

Every time you sit in clear awareness, you have stepped a little closer toward your own

enlightenment.

All Buddhist practitioners and others who have come into contact with

Buddhadharma have already planted seeds for their future

Buddhahood. In fact, people who oppose Buddhism have also planted

seeds for their future Buddhahood. How so? Sutras say that anyone who slanders

the Buddha or the Dharma will spend time in hell. When they realize why they are

in hell, perhaps they will reconsider and change their minds about Buddhadharma.

I have told the story of a Sung dynasty official who hated Buddhism and wished

to discredit it in a scathing article entitled, "The Non-existence of the Buddha." For

months he racked his brains trying to think of reasons that would

refute the existence of the Buddha, but he could not do it. Finally his wife suggested that he study

the sutras and sastras so that he could better organize his own ideas and feelings.

He agreed, and began to study the sutras. Eventually, he had a change of heart and

mind and became a great lay practitioner. People who accept and practice the Dharma

have chosen a direct route to Buddhahood. People who oppose the Dharma have

chosen an indirect route to Buddhahood; nonetheless, they are on their

way. It is the people who do not care at all and who know nothing of

the Dharma who have not yet found the path. Even so, it can change

in an instant if they open their minds and hearts to the teachings of the

Buddha, in this or any other world and time.

For Chan practitioners, however, these are all metaphysical

speculations. They have nothing to do with the important matter of being absolutely aware in the present

moment. The best way to plan for your future Buddhahood is to take care of the

present moment, and not worry about how good or bad a job you are

doing. All great masters down through history followed a similar

path, and they all met four conditions: they made great vows,

they had great faith, they had great determination, and they generated great doubt.

We can walk the same path by meeting these four conditions. First, make vows

that will strengthen your faith, determination and will. The Four Great

Bodhisattva Vows are a great place to start, but you can also make individual vows that will

help to strengthen your practice. Second, develop great faith in the Dharma,

in the teacher or teachers you decide to follow, in your method of practice,

and, most importantly, in yourself. Third, with great faith and the power generated by your

vows, you will cultivate great determination in your practice, and eventually,

this determination will give rise to great

doubt.

Some of you have said that you feel hypocritical making vows you cannot keep.

Do not be disheartened. For many of us, the Four Bodhisattva Vows are

unimaginable in their depth and meaning. Nonetheless, you should take these vows because

they plant seeds that will someday sprout. Vows help to make your practice

stronger. Do not even despair if you cannot keep your own individual vows.

Each time you approach your cushion, bow to it and make a vow: "I will not be moved by

pain," "I will not be overcome by sleepiness," "I will not be distracted by

wandering thoughts." If you make these vows with sincerity, that is enough.

Then forget about them. Have faith that the seeds planted by these vows are within

you, and then put your mind on the task at hand:

your method. If, during the sitting, you are overwhelmed by pain in your legs or

back, then do what you feel you must. But if you do move, do it with the same

sincerity you used when making the vow. When the sitting is over, do not chastise yourself

for breaking a vow. This is the process. Next time you begin to sit, make the same

vow again. In this way, you will slowly but surely strengthen your determination.

People are forever missing the point when it comes to practice. It is because you

cannot keep your vows that you should keep making them. If you could meditate

for hours without being moved by pain, drowsiness, or wandering thoughts,

then there is no point making a vow about such things. Every Buddha of the past and

present followed the same path, making vows hundreds and thousands of times until they

accomplished their goals.

People are also often confused about great determination. They think that being

determined is at odds with being relaxed. It is not the case. Determination does not mean

being tense and coiled like a tight spring. Determination means being patiently

persistent in your approach to the method. When you find yourself off the method,

bring yourself back, but do so in a gentle and relaxed way. Approaching the method

in a tense manner will lead to exhaustion and other physiological

obstructions. Tension is a hindrance to practice. That is why I always say, "Relax your body and mind,

and work hard."

When you plan to climb a steep mountain whose summit is miles away, what is your

strategy? Are you going to treat it like a hundred-yard dash and start sprinting up

the mountain side? I guarantee you will not get very far. Better to walk at a slow and

steady pace, and plan on camping overnight for a few days. But once you begin,

you should not dwell on thoughts about what you might experience in a few days

when you reach the top. Once you begin, your mind is on one foot in front of the

next.

Meditating is the same as climbing a tall mountain. Do not worry about anything

else but your own method. Do not compare yourself to others. You have your pace,

others have their pace. You have no idea what they are experiencing, and it is no

concern of yours. Just use great determination to keep your mind on your affairs.

Once there was a Chan monk who was plagued by drowsiness. He would forever find himself nodding off on the cushion.

He decided on a risky strategy and sat at the edge of a tall cliff. "If I doze

off, I will fall to my death. That will keep me alert," he thought. So he

did, but nevertheless, he got sleepier and sleepier. Finally, he dozed off and fell off the

cliff. As he was falling, he awoke and instantly got enlightened; then he realized that he was still sitting at

the top of the cliff. If you wish to use this technique, you can sit on the

third-floor

window sill. How sincere and determined are you? Will you want a safety net?

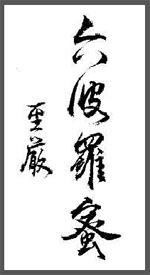

The Six Paramitas

Commentary by Master Sheng-yen

This is the first of three talks

by Master Sheng-yen on the Six Paramitas, given

at the Chan Meditation Center,New York,between June 7 and June 21,1998.

The remaining two talks will be printed in

subsequent issues. The talks were orally translated by Ven.Guo-gu Shi,

transcribed by Tan Yee Wong, and edited by

Ernest Heau, with assistance from Tan Yee Wong.

David Berman copy-edited the final text.

Buddhism can be approached by studying the teachings and by practicing the teachings. It is not always easy to distinguish between the two. Deliberating upon and profoundly discerning the teachings can, in itself, become a way of practice.

Similarly, practicing to attain wisdom (prajna) requires stabilizing the mind (samadhi) through understanding the teachings. Study and practice, like prajna and samadhi, are thus intimately connected. Buddhism can be approached by studying the teachings and by practicing the teachings. It is not always easy to distinguish between the two. Deliberating upon and profoundly discerning the teachings can, in itself, become a way of practice.

Similarly, practicing to attain wisdom (prajna) requires stabilizing the mind (samadhi) through understanding the teachings. Study and practice, like prajna and samadhi, are thus intimately connected.

Hinayana and Mahayana

By a hundred years after the Buddha's nirvana, approximately twenty different schools of Buddhism had arisen and had begun interpreting the teachings in different

ways. About 400 years later, Mahayana (Greater Vehicle) Buddhism first appeared, and distinguished itself from the earlier schools by referring to them as Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle).

"Hinayana" refers to those Buddhists who mainly practice the Four Noble Truths and the

Thirty-Seven

Aids to Enlightenment, and "Mahayana" refers to those who also engage in the Six

Paramitas and the Four Ways of Gathering Sentient Beings. However, there is no

scriptural basis for the distinction between Hinayana and Mahayana. In fact, the earliest Buddhist scriptures (the Pali nikayas

and the Sanskrit agamas) encourage the practice of the Four Noble Truths and

the Thirty-Seven Aids as well as the Six Paramitas. The early schools did not refer

to themselves as Hinayana, and the term can be viewed as derogatory if used by

Mahayanists to designate other Buddhists as practitioners of a lesser path.

Nevertheless, on closer examination we do see a meaningful distinction in that Mahayana Buddhism places a greater emphasis

on generating a supreme altruistic intention to help others. This aspiration to

alleviate the suffering of others without concern for one's own nirvana is the anuttara (unsurpassed)

bodhi-mind. While diligently practicing the Dharma, such a practitioner realizes that nirvana is not a

blissful, abiding state in which one rejects samsara, the existential realm of suffering.

Without rejecting or clinging to nirvana, the bodhisattva vows to return to the

world to help sentient beings. This is the correct attitude on the Mahayana path. As ideals of this we have Manjusri, Bodhisattva of Wisdom;

Samantabhadra, Bodhisattva of Great Actions and Great Functions; Avalokitesvara, Bodhisattva of

Compassion; and Ksitigarbha, Bodhisattva of Great Vows. These great bodhisattvas vowed to help

sentient beings reach liberation before attaining their own buddhahood. Therefore, if there must be a distinction between

Hinayana and Mahayana, it should be based on the bodhisattva's more expansive scope of mind rather than

on one's methods of practice.

At the time of the Buddha and after, the idea that the ultimate goal of practice was

to transcend this world and attain nirvana was very prevalent among practitioners of

Buddhism, and of other paths as well. This idea of abiding in a heavenly realm is also

common in many Western spiritual disciplines. It was from this attitude that the

Mahayana followers wanted to distinguish their teachings by using the term

"Hinayana."

Some people, of course, are so attached to the material and sensual delights of this

world that they do not want to leave it. Their attitude is, "Why would anyone want

to leave this wonderful world?"

But bodhisattvas realize that even as people immerse themselves in sensual delight,

they create unending afflictions for themselves and others. They realize that the

world is characterized by inherent suffering, and they wish to end the cycle of suffering for themselves and for others; they

have aroused a desire to help others break free from the cycle. Realizing they have

awoken from false dreams, they want to help others awaken too. This is the proper

attitude of bodhisattvas. When we reflect on their sincerity and genuine intentions,

we feel quietly touched and thankful.

Practicing the Paramitas

In Sanskrit "paramita" literally means "having reached the other shore." It also has the meaning of "transcendence," or "perfection." If we exist on the shore of suffering, reaching the other shore would mean leaving suffering behind and becoming enlightened. Transcendence thus means to be free from mental afflictions, the causes of suffering, and from suffering itself. To truly practice the paramitas is to be free from

self-attachment and self-cherishing. Based on this definition, the Four Noble Truths and the

Thirty-Seven Aids to Enlightenment can also be considered paramitas, because they accord with the teachings of

non-attachment and no self-cherishing. All Buddhist practices can thus be viewed as paramitas as long as they accord with the above principles.

From the Mahayana standpoint, to practice the paramitas is to practice in accordance with selflessness and

non-attachment, and for the dual benefit of self and others. If practice only benefits oneself this cannot truly be paramita practice. Therefore, if a person does not practice to benefit others, whether their practice is called Hinayana or Mahayana, they are not truly practicing the

paramitas.

Except for a few to whom helping others is of primary importance, most people believe in defending and caring for themselves first. After a lecture I gave on the Six Paramitas, a gentleman said to me, "I never entertained ideas of benefiting others, because I am feeble. If I can't help myself, how can I vow to deliver others? I would be very happy if someone could help me. But it is not possible for me to help others."

The truth is that when you seek to benefit only yourself, what you can reap is limited. Your own rewards will be greatest when you strive to benefit others. As a simple example, if you seize all the wealth in your own family

-- from brothers, sisters, husband, wife or children -- how will you survive in that

household? Conversely, if you are careful and considerate of your family members, they will be appreciative and reciprocate. Your family will become very happy and harmonious. Therefore, Buddhism espouses benefiting others as the first step on your path to liberation. Still, the best approach is not to be overly preoccupied with helping others, but simply to practice Buddhadharma with diligence. The benefits from helping others will flow naturally from that. The Six Paramitas are precisely the means to do this.

What then are the Six Paramitas? They are: generosity (dana), morality (sila), patience (ksanti), diligence (virya), concentration (samadhi), and wisdom (prajna). Their purpose is to eradicate the two types of

self-attachment, to sever the two types of death,and to transcend the ocean of suffering.

Self-Attachment

What are the two types of self-attachment? The first is attachment to one's own body, the extension of which is the concept of our life span. The five skandhas

-- the material and mental factors that together lead to our sense of self -- are the fundamental source of our vexations and afflictions. To break away from this self through practicing the Six Paramitas is to give rise to wisdom that will sever the attachment to one's physical body. Eradicating this kind of

self-attachment means transcending our illusions about the world.

The second type of self-attachment is aversion to the afflictions and sufferings of worldly existence. Eradicating this type of

self-attachment means transcending our aversion to the phenomenal world, and no longer fearing the cycle of birth and death.

Death

What are the two types of death? The first is the physical death ordinary people experience as they migrate through samsara

-- the cycle of birth and death. The second type of death consists of the stages of transformation on the bodhisattva path. There are ten such stages, or bhumis, that a bodhisattva traverses on the way to buddhahood. Bodhisattvas experience samsara, but their death is not the ordinary physical death referred to above. It is, rather, the death of progressively subtler layers of attachment that are shed as great bodhisattvas progress through the bhumis, transforming their own merit and virtue, and finally attaining the dharmakaya, the body of reality, perfect buddhahood. The tenth and last stage is the complete fulfillment of all practices and realizations; thereafter transformation death will not recur. In accordance with the ten bhumis, the bodhisattva practices the Ten Paramitas. Thus, when you generate

bodhi-mind, the altruistic mind of benefiting others, you benefit yourself as well.

The First Paramita: Generosity

The practice of generosity, dana, can be traced to the early teachings of the nikayas, the agamas, and to the later teachings in the Prajnaparamita Sutras, as well as the Mahaprajnaparamita Sastra, which elaborates in detail on this practice. Among the paramitas generosity can be the easiest

to fulfill. One can reap immediate benefits from this practice, which can be practiced in two modes: with characteristics and without characteristics.

Generosity with Characteristics

We practice generosity with characteristics when we have a motive for performing a generous deed. For example, we can give as a form of repayment for something received. We may feel indebted even though the giver does not expect anything in return. We may even do charitable work or make donations in the name of that person. We may then say that we have fulfilled our indebtedness. This kind of giving is good and may be counted as generosity. I have a disciple who attended a

seven-day retreat with me in Taiwan. Afterwards I asked him why he came to the retreat. He replied that his wife was extremely good to him, and he asked her what he could do to express his gratitude. She told him the best thing he could do for her was to attend a Chan retreat with me.

So, his motive for coming to retreat was to repay a debt to his wife. [Laughter ] You could say this is practicing generosity with characteristics because it was a good deed that nevertheless had a motive.

Generosity with Characteristics and Intention

Generosity with characteristics and intention is giving with the intention of being recognized, being reciprocated, or earning spiritual merit. (Spiritual merit is experienced only after death, in a heavenly realm.) While these types of generosity are a little selfish, like

investments, they are still good, and better than not giving. There are people, after

all, who are miserly, yet expect others to be generous to them. This is like constantly paying for things with your credit card. Somewhere down the line, the account must be repaid, and with interest.

The paramitas are antidotes for different kinds of mental afflictions, and the cure for greed and miserliness is generosity. Miserly people may feel that they benefit themselves when they get the upper hand, when in reality they are harming themselves. Their strong possessiveness prevents them from receiving the rewards of helping others.

The Sickness of Poverty

While this may sound strange, the poor should practice giving as a way of freeing themselves from poverty. What can a poor person give? How can his condition be improved by giving things away? Even poor people can work very diligently to benefit others. Through diligence they will acquire what they do not have and they will gain what they lack. In the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra, Nagarjuna Bodhisattva uses the analogy of a thirsty person who, being wrapped up in

self-concern, does not know how to find water. But if someone has a strong intention to bring water to those around them they will very diligently look for water. Because of their intention, they will tend to find more water than someone only concerned with his own thirst. Similarly, those in poverty are more likely to find wealth if they work diligently to benefit others. The Daoist sage, Laozi, had a similar idea that one can gain the most by giving everything to others.

Giving Without Characteristics

Giving without characteristics means giving freely, without self-oriented motivation. It includes the gift of wealth, the gift of the Dharma, and the gift of fearlessness.

The Gift of Wealth

The wealth that one may give freely and without characteristics includes material wealth, time, knowledge (including speech), and one's own body. Giving material wealth, including money, is fairly obvious, but giving one's time and knowledge are also ways of practicing the first paramita. For example, for a very wealthy person to give a little bit of money may be less meritorious than for a poor person to give a lot of their time and knowledge. Giving one's body includes one's strength and

energy, but it also includes literally giving part of one's physical body, such as skin to burn victims, or an organ to be transplanted. You can be an organ donor while alive, or after death. But when you are alive, you would want to consider carefully before donating any parts of your body.

The Gift of the Dharma

People who think that the Dharma is something very mystical and abstract can become very confused about the idea of giving the Dharma. In fact the Dharma is nothing other than the teachings of Buddhism. For example, the teaching on dependent origination is that all existence is a result of interdependency. Something exists because it is the product of other causes and conditions, and this something will in turn condition the arising and existence of other things. Since everything is constantly under the influence of something else, nothing truly exists independently, and nothing is permanent. How do we relate this to our own

lives? Here is a simple analogy. The reason one is a wife is because one has a husband. If one does not have a husband, one is not a wife and vice versa. Therefore, husband and wife are interdependent, relative to each other. If you present this teaching to other people, then you are giving the

Dharma. You need not literally tell others about the theory of wives and husbands; you just need to communicate the idea of this thing being dependent on that, and vice versa, or this ceasing to exist because of that, or the perishing of this causing the cessation of that. So, simply by sharing your understanding of the Buddha's teachings, you are giving the Dharma.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has said that if a person understands dependent origination they understand the Dharma. If they understand the Dharma they understand Buddhism. If a person correctly expounded this idea, it can be considered giving the Dharma.

The Gift of Fearlessness

People fear many things -- death, poverty, illness, imprisonment, and so on. The gift of fearlessness is being able to respond to people's fears and needs with wisdom and compassion. As practitioners of the paramita of giving,we can alleviate people of their fears, whatever their origin.

Hammerstrasse on 20 July 2001

Poem by Max Kalin

Morning at five

The road deserted, I walk its middle

Everything is gently present

Road, intellect, no-traffic,everything

Then I know that I know, free of doubt

The universe of matter

From the simple to the complex

from the fundamental to the compound

And the universe of mind

From the subtle to the coarse

from the whispering to the talking

Go hand in hand

Cannot be without one another

Mind activity is function of material flux

Material flux is function of mind activity

There is neither cause nor effect

The material at all levels and in all forms

And the mental at all levels and in all forms

Are like either side of a road

But the middle is because of either side

And the middle is because of the thirst to be

And that thirst has a myriad of faces

And below and above the middle is more of less

And the less leads to neither whispering nor not-whispering

There, beyond limit and no-limit, is the end of the road |

"Really Not There Anymore

"

Retreat Report by A.R.

I'm sitting here, in this place that I cannot call home, even though it has an address. Phone calls for me

to come to it, and whatever stuff I'm left with from my life is in it on shelves and in boxes. I don't see in it what I saw in the home of my childhood, or the home in which I raised my children, years ago. Then it seemed that just like us, having a body

box, inside of which there are emotions, heart, intentions, warmth, kindness,

inclinations, good will, fatherhood or motherhood, so also a home, even though it is nothing but walls around air, has inside of itself some emotional center. I cannot look at it this way anymore.

I know that all we are is nothing but some kind of an imagined entity, hanging in some kind of endless space, that does not move. I think that I exist, and I exist. I'm nothing but a wandering thought.

And all the others too. And because every one of us has a different set of reaction habits, and because of not being free, but rather

inflexible, we bounce into each other all the time. Sometimes we love, sometimes we are angry, we embrace, run away, or run after.

I am homeless, because there is not such a thing as home. How long will it take until my behavior will harmonize with my knowledge?

There is nothing substantial in all bodies. They are not it.

When Shi-fu goes today to Taiwan, he really does not go anywhere. He does not move. Just like us, when we went with him to see the lake and the stream, and really nothing happened. The quietness among the trees, the spaces of bright sky among the branches evoked their paired experience of the spaces among phenomena in our awareness. When we look there we find that the sense of reality is not an undisturbed continuum, but on the contrary, there are many spaces among phenomena.

When we look in the spaces, we find the place where nothing is, where there is no sense of reality. This is where the incomparable silence is. Whatever appears on its surface is an impossibility. If we want, then everything exists. If we harmonize with the silence, it becomes clear that there is no reality in what we see in front of us, just like in a dream.

I walk on the grass and look down. There is the small circle of my field of vision. In it are the feet of the one in front of me, parts of my own body, and grass. A changing picture. I feel as if I'm wrapped in awareness, inside of a knowing. As if I'm swimming inside something that is between milk and smoke. Inside this awareness everything is known. All of

me, like a transparent bubble, with my emotions, a few thoughts, and this movement that is also a will that does not exist. There is no escape from this knowing of myself as an unbelievable thing. The grass that bursts out in its endless variations cannot be.

My weight pulls me capriciously downwards. A truck comes and disposes a load of gravel. Then it leaves and is not there anymore. Really not there anymore. So clean.

I'm sitting on the fifth morning. I'm tired and achy. I don't yet start falling to the

right, as will happen later. Right now I'm touching with my mind this awareness that's around

me, and slowly, slowly it purifies into something that I cannot describe. Inside this everything is, including me, with all my sensations. Again everything is totally known. I'm reduced to three points of sensation

-- that's what is left of me. The

world, the woods, all existence cannot be so pure as this. Everything is just wandering thoughts. Especially me. I stay like this, touching this purity for some time, until the bell rings for the morning service. I can go on very easily. It is so easy. But I decide to stop for some reason. The thought: At last the meditation started working. I'll be able to return to it with no difficulty later. But I can't. It's always like this. In the moment it does not look like anything special. Later it does.

Coming out of it I have one thought: After seeing this, there can be no justification whatsoever for doing anything that is not the most beautiful that I can possibly do. What's the point of doing anything that is less than this?

I depart from Shi-fu, who is about to fly to Taiwan today. I want to embrace his body, and I know that in my heart I already do it, and that he knows. His body is getting old, but how older can eternity get? Was it ever young?

Apart from these, all my sittings were difficult and full of pain. I struggled with a method whose secrets I haven't come to know yet.

I don't understand this whole existence. What is going on here? I am going to be a Buddha, and then I'll free endless numbers of people, who in their turn will also be Buddhas, and others will come in their place, and so on endlessly, like a topological shape, or a Moebius ring. What is the sense of this all? Why advance at all? What difference does it make? I know, on the other hand, that I have no choice. The more I know, the stronger my direction is determined. The best I can do is harmonize with it.

When I suffered I thought: Why do I go to these retreats again and again? My body does not take it so easily anymore. For a minute I imagined myself without retreats, and then I thought: What else have I got to do with my life? What else is there that's worth living for?

The last morning of the retreat. Again we sit in this unbelievable cold. I get up, ready for the morning service, and see that all my friends in this room are not their bodies. Their bodies are not them. Only their thoughts are them. How funny. But it feels holy for some reason.

Several times it came to me, that I would like to be one of our neighbors. To be in his home, in the silence of the wood, so early in the morning, and hear our morning chanting, coming through the trees, and this will wake his longing for the truth.

I cry when I write it. How many times did I feel this longing, and saw this picture so clearly: I sit in meditation on the top of a mountain, I see myself as a silhouette while the background is light, and I dissolve into the universe. I wrote a poem with this picture in it when I started sitting, not knowing what it means. Do I know now?

Shi-fu speaks about this funny koan: The ox is eating in one place, and the horse is becoming satisfied in another. After having fun making us try to solve it he explains at last that it has to do with an experience of enlightenment, in which the realization is that everything is just the way it has to be.

I remember that I had an experience like this many years ago, when I was in Israel, and did not have children yet:

My wife says again and again that something is wrong with me. Everything is wrong with me. The whole of me is wrong. I love her desperately, and believe that she is right. Everything is wrong with me. I don't understand why, and also not what, but feel that truly something is deeply wrong. All my life, and I don't exactly understand how, did not come out right. In deep despair I leave home, and climb a nearby hill, walking on a dirt

road. On the top of the hill there are a few wild pines. I look at them on the background of the sky, and suddenly I am overwhelmed by a deep peacefulness. Everything is OK, I

know, and it is so clear. Everything is just the way it has to be. There is no problem whatsoever. It seems that everything was already. My life is not going anywhere. And yet I go.

Noble Truth

A True Story by Mary Rapaport

I lay next to her in the bed as the day softly faded, holding her in my arms, and inhaling her pure, clean scent. Killeen, my

four-year-old daughter, my treasure.

Curling up next to me at bedtime, she smelled faintly of grass and popsicles and of her own, fresh sweetness that I had remembered from the day she was born. We lay in contentment, heads sharing the same pillow. Her little, nimble form, spooned close to my body.

"Mommy, I just don't know why Jocelyn doesn't like me."

I sighed, and kissed her lightly on the forehead. My heart ached with wanting to protect her and take away her hurt.

"She's mean to me all the time. Maybe she doesn't know I like her."

Over the past year, I'd come to know much about my daughter's unrequited love for Jocelyn. A nemesis, not quite an enemy, to Killeen, Jocelyn was a consistently unattainable friend. A

"pre-kindergartner" and thus an upperclassman, my daughter had admired Jocelyn since her first day of preschool.

An expert in playground rules and an authority on school yard alliances, Jocelyn was special to Killeen and achieving her friendship and acceptance was my daughter's Holy Grail.

Perhaps unconscious of the power she had over my daughter, for over a year Jocelyn had seemed to dangle the carrot of friendship and acceptance in front of Killeen. Sometimes the prize was within reach, and Jocelyn invited Killeen to play with her clique. More frequently, though, Jocelyn seemed prone to slip just out of her grasp, not playing with, and often ridiculing members of the

pre-school "freshman" class.

Each day, the drive home from pre-school was seasoned with accounts of what Jocelyn had done or said, and how she had treated Killeen.

From all reports Jocelyn was as changeable as the weather. On days when Jocelyn would play with

Killeen, music was in the air, the sun was shining, and the world was a better

place. Today, however, the Jocelyn forecast had definitely been at least partly cloudy.

"I don't know why she is so mean to me. I tell her I like her, but she just keeps being mean."

Although I've heard this many times, I've really never known quite what to

say. How can I explain about wanting something or someone who just doesn't want you back?

Do I tell Killeen that no matter how special Jocelyn is to her, she isn't, and may never

be, very special to Jocelyn?

How do you explain that sometimes you can't work harder, you can't be

nicer, and no matter how good you are, you can't do anything to change the way someone has decided to feel about you?

In memories, I could see myself on the playground, looking wistfully at a group of "popular"

girls, admiring them, wanting to be like them, wishing they would play with

me, wanting them to accept me. I knew I'd never belong to their clique, but knowing it didn't make me want it any less. Was it starting for her already? What's the Buddhist

lesson? Anything I could use?

"Suffering is wanting things to be different from what they are." Say,

this seems to apply here. But how do I pasteurize and process it for the consumption of a

four-year old?

"Well," I begin, "I don't think you can make Jocelyn like you, but I have an idea about how to make it stop hurting when Jocelyn is mean to you or doesn't play with you."

"What is it?"

There is a tiny bit of tension in her body. I know she's anticipating the

ANSWER. She believes that Mommy has THE SECRET. The magic words. Am I up to this pressure?

"Maybe you can try to stop wanting Jocelyn to like you."

There is silence.

We are both contemplating this amazing concept that is also the Buddha's fundamental teaching.

Can it actually work? Will the idea of dropping attachments make sense to a

4-year-old, who I've seen cling to absolutely everything she can't have - whining for that second lollipop she isn't supposed to eat or hanging onto my arm every time I drop her off at

pre-school?

Tell her to stop wanting? Will she buy this?

To my surprise, Killeen doesn't try to argue the logic of the idea.

Breaking the silence, she wants to know just one thing.

"How?"

Now I'm speechless. And though I should have seen this coming, I have absolutely no idea what to tell her.

If I knew HOW, I wouldn't have half the conflict in my daily life. I wouldn't have to make visits to the temple or meet with my teacher. In

fact, my teacher would probably come to me.

"How" is a damn good question. And Killeen, surprisingly patient, is quiet, still and waiting for me to answer.

"Well," I begin," Maybe rather than thinking all the time about how Jocelyn doesn't like

you, you could remember how much your friends, Mary Elizabeth and Isabella do like you."

I pause in my explanation. I'm not at all sure how this is going to play

out, and I'm trying desperately to think of another way to put it.

To my surprise, she decides to run with the ball.

"Mary Elizabeth and Isabella really DO like me." She smiles.

Yes, they are probably your best friends, aren't they? They're really nice to you, they play with

you, and they like you so much."

I can feel her body relax. She is actually beaming.

"Yes, they are good friends. We had such a good time together today."

And just like that, she has let it go. Her suffering ends. She is joyous.

She yawns and rolls over. We snuggle close. She presses her little self even closer to her Mommy.

As I lay next to her, relaxing in the sleepy music of her soft breathing,

I am overwhelmed to see the Noble Truth that is right in front of me. In letting go of what she didn't have, her conflict and pain just disappeared.

With her Mommy close and her real friends wanting to play, she is able to sleep in freedom and contentment, knowing that right

now, her life is perfect exactly as it is. But I know I'll hear more stories about Jocelyn tomorrow, and this realization is another kind of truth.

By tomorrow morning, my daughter will again start to wonder what it will take to get Jocelyn to like

her. Because by tomorrow morning, she will have forgotten all about how good it felt to stop wanting to be Jocelyn's friend.

And what will I say to her tomorrow? And what will I tell her as she grows and the questions become more complex? Being her teacher

-being "Mommy "is such an awesome responsibility.

Eventually, smiling, I close my eyes, relax, and snuggle next to her little slumbering sweetness. I drift off, watching her peaceful

form, breath rising and falling, marveling again that it was she, not I, who had just let it go.

(Mary Rapaport is a writer, and a new student of Soto Zen Buddhism,

practicing with Deep Spring Temple. She and her family live in Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania.)

Songs of the Wanderers

Poetry by the Buddhist Youth Group

|

|

|

|

| On

November 5th of last year, Chan Center member Lindley

Hanlon took members of the Buddhist Youth Group

to the Brooklyn Academy of Music to see a performance

of Songs of the Wanderers by the Cloud Gate

Dance Theatre of Taiwan. The following poems were

written in response to that performance. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Songs of the Wanderers

A Buddha calm and peaceful standing there

relaxing, no sound.

Wanderers showing their pain, greed and need

for things that cannot be given.

Twirling in a life cycle first a deer.

Boom, boom, hunters are here.

Reborn next day deers are hunters, hunters are deers.

This is the twirling and whirling life cycle of nature.

Hope comes to all people once they have the fire gift.

Wonders lie before them for them to sooner find out.

Once there was a blinding smog before their eyes

to blind them from the truth of love and peace.

There, look, a man that has patience,

drawing circles in the rice,

showing how everything keeps going on and on.

Suddenly when the circles are done

the lights brighten and there's a big applause.

This is the sign that

this wonderful deep feeling play has ended.

Now we're stepping out the door and out of

the song of the wanderer's song.

- Monica Feng, age 11

|

|

|

Changes

There, it changes, and there,

slowly it changes again as they move,

showing no movement

yet changing in a way

only they can see.

With no thought, they glide slowly

across the stage.

Seeming so close but yet miles away

from their goal and then,

it changes...

to what looks like suffering

and need and unhappiness then changes,

but how?

Are they showing pain or joy?

Then you know,

it just comes to you, it changed...

They show no sign of it,

you just know it... It changes...

- Nicholas Steele, age 11

|

Chan Master Sheng-yen at the

U.N.

Translator Rebecca Li reports

on the United Nations Millennium World Peace Summit

In August of last year the United Nations hosted the Millennium World Peace Summit of Religious and Spiritual Leaders. More than a thousand leaders attended the summit from all over the world, and Master

Sheng-yen was invited to be one of the keynote speakers. I had the good fortune to attend the event as Shifu's translator, and thus to learn from his speech and conduct for four full days.

At the press conference the first morning of the summit, a reporter asked Shifu to comment on the relevance of walking meditation to the summit's theme of world peace. (The question was asked because Thich Nhat Hanh, who could not attend because of his retreat in California, was going to lead a walking meditation for the summit that afternoon while several dozen religious leaders said prayers.) Shifu's answer gave me a whole new understanding of walking meditation. He said that we can take the mindfulness cultivated in walking meditation into every aspect of our daily lives, and once we have inner peace, we can then promote peace outwardly to our society and to the environment. Essentially, world peace starts with peace in our own mind.

A reporter from a Chinese newspaper asked the question, "What is ‘Understanding the Mind and Seeing the Nature

'?" I thought we were in for a complex Dharma talk explaining these concepts, and could not believe the simplicity and clarity of what I heard. Shifu said that we should not think of these experiences as mysteries: "understanding the mind" means knowing that one has

vexations, and "seeing the nature" means seeing that one's mind is constantly changing and that its nature is empty.

Right after the press conference, Shifu was scheduled for a videotaping session. The producer was interested in the reasons that Shifu had devoted his life to spiritual practice, and what he thought religion can do that government often cannot. When asked about the significant events that led him to devote himself to religious life, Shifu recounted his experiences of war and natural disaster when he was still a little boy, where he saw the fragility and impermanence of human life. Having seen how much suffering there was in the world, he knew he wanted to devote his life to helping people.

Then the interviewer asked Shifu how individuals like himself, who are devoted to a spiritual life, can help promote world peace. Shifu pointed out that religious leaders are not isolated from ordinary people; they are intimately related to their followers and thus know clearly the problems of the world. What religious leaders can do that government cannot is teach concepts and methods to help people help themselves. Shifu illustrated his ideas by describing his work after Taiwan's earthquake last year, and by describing the four kinds of environmental protection he advocates in Taiwan: (1)purifying the mind to eliminate greed, hatred, and ignorance through methods of meditation and contemplation; (2)being mindful of one's conduct and speech in social interactions, which also involves simplifying and dignifying group ceremonies such as weddings, birthdays and funerals to change current wasteful practices; (3)extending our compassion outward to all beings and our environment, which requires transforming our current wasteful and lavish lifestyle into one that is simpler and more

Earth-friendly; and (4)conserving and protecting precious resources in our natural environment.

Early on the morning of the second day, Shifu was invited to participate in a meeting with other Buddhist leaders. The meeting was attended mostly by Theravadan monks, along with several Japanese masters, who espoused many different viewpoints about Buddhism in their respective countries, and about

spreading the Dharma to the West. Throughout a heated discussion, Shifu sat patiently with a smile, mindful all the while of his obligation to leave on time for the summit. When he had to leave the meeting, he was invited to say a few words. As

always, Shifu's words were succinct and to the point, and in this case, especially relevant to the theme of the summit. He said that we should see all Buddhist schools as one family, and that we should see all other religions as members of the family as well, because what is important is not what one espouses and believes, but what one actually does.

Finally, the keynote speakers from all over the world began to speak in the General Assembly Hall. Although each speaker was given a set amount of time, few followed the rule, and the program was running seriously overtime. The organizer asked speakers to stick to the time limit but to no avail. Most of them ignored the bell that indicated time was up and stuck to their prepared speeches. People began to get impatient and frustrated. Shifu's turn came, and he tried to speak quickly, but the timing bell rang when there were still two paragraphs to go, and Shifu wrapped up his speech in two sentences and got off the stage immediately. When most people wanted to stay on the stage for as long as possible in this big event, he cut his talk short for the benefit of others. (For the full texts of Shifu

's speeches given in the sessions "A Call for Dialogue" and "Environment: Religious Perspectives for a Sustainable Future" see the Fall 2000 issue of Chan Magazine or visit the

online issue.)

The third day of the summit was supposed to be one of rest after two days of intense activities. Shifu thought we might just attend a couple of working sessions on poverty or conflict resolution and take it easy, but it turned out to be the most intense day yet. Late in the morning, while taking a break in my room, I got an urgent call from Guoyuan Fa Shi "the organizer of the summit had called a special meeting with only a few religious leaders, including Shifu, and I had to go translate. The meeting turned out to be what Shifu called the

"high-level talk of the high-level talk." In the boardroom of the Waldorf Astoria sat leaders from large world religious organizations. Interestingly, Shifu was the only Buddhist leader in the room. The goal of the meeting was to discuss the formation of a World Religious Leaders Advisory Council that will serve as a resource for the United Nations

secretary-general. There was heated discussion of the role of the Council, what its mandate should be and who should be included. Because of the potential influence of the Council, there was great interest among the participants to be included. As a result, everyone was eager to participate in the discussion, and the meeting took all morning and all afternoon. At the end, the meeting came to a consensus that there should be an interim committee of six to ten individuals who will be charged with further discussions of the role and goals of this advisory council and report back to all the participants within three to six months. There followed a long discussion of the criteria that should be used to select the individuals for the committee. Shifu had been listening patiently, but finally broke his silence to say that this council should not be a group that wields its own power, but rather one that serves the United Nations. As for the selection of committee members, he said, it was not necessary that such individuals be powerful or influential, but they should possess the wisdom, compassion and skills necessary for the job. Just a few simple words, yet everyone in the boardroom broke into applause, and adopted these as the criteria for selecting the committee.

The long meeting in the boardroom was followed by a meeting with the vice-chairman of the World Bank (Katherine Marshall) and the coordinator for the Faiths of the World Faiths Development Dialogue (Wendy Tyndale). Both of them had organized sessions on poverty during the summit, but had found what was said in the presentations wanting. In this meeting, therefore, they asked Shifu to give them advice on how to deal with the world's problem of poverty. Shifu first clarified the definition of poverty, pointing out that it has both material and spiritual aspects. While we tend to focus on material poverty only, it is spiritual poverty that really causes suffering.

Shifu addressed the problem of material poverty by using the analogy of fishing. When a group of people are

starving, they cannot be taught how to weave fishing nets. We must first give them fish to eat, and then teach them how to weave their own fishing nets and use them so they will be able to feed themselves.

The problem of spiritual poverty is actually more difficult to handle. We should teach people proper attitudes with which to face the situations in their lives. Shifu used his own parents as an

example. Materially, they were very poor, but they were also very generous. When they saw others without food, they shared, and felt grateful that at least they had something. Shifu suggested that we train people to live compassionately among the poor, teaching by example, and that we also teach methods to calm the mind in order to help people deal with emotional suffering.

The last day of the summit, Shifu spoke to a working session on the role of religion in environmental protection, and that same evening boarded a plane for Taiwan, with a full day of press conferences and meetings waiting for him. I was exhausted, but I knew that my fatigue was nothing compared to Shifu's. His devotion to spreading the Dharma without regard for his physical condition never fails to inspire me. The summit had been a truly memorable experience. Seeing and meeting so many spiritual leaders from all over the world was remarkable in itself, but I felt especially fortunate to have been so close to Shifu as he used his wisdom and compassion in so many difficult situations. I hope I have succeeded, at least in small ways, in sharing the precious jewels I was able to collect by being there.

The Past

September 11th – CMC Mobilizes

Even as we are shocked and horrified by the events of September 11th, we are fortunate to be able to report that the Chan Meditation Center's immediate family

-- our members, regular participants and their families -- are all safe, unharmed by the terrorist attacks.

Master Sheng-yen, in Taiwan when the attacks occurred, said, "While praying for the victims of this tragic event, we hope that the public will face the event rationally, and will not further the conflicts between nations and religions with deeper hatred. With great love and compassion, we ought to protect the prospect of future peace for all humankind." Shifu called on religious leaders worldwide to pray for the victims of the tragedy and to work to ease people's fears and calm their minds in its aftermath. He also

re-iterated a point he had made during last year's Millennium Peace Summit of Religious and Spiritual Leaders, saying, "If one finds that the doctrines of one's faith contain something that is in conflict with the promotion of peace, one should make new interpretations of those relevant doctrines... Since all religions advocate peace, forgiveness, love, departing from hell and entering paradise, such ferocious acts should never have occurred."

Meanwhile, here in New York, on the evening of September 11th, Guoyuan Fa Shi performed a memorial service for victims of the attack attended by more than a hundred members and friends of the Chan Center. On September 14th, in response to the President's call for a National Day of Prayer, CMC conducted a second memorial and prayer service for 150 participants. In the days that followed, Guoyuan Fa Shi conducted special prayer and memorial services at the Flushing Library; at the Kwang Ming Temple in Chinatown; at the DDMBA chapter in Virginia Beach, Virginia; and at the New School University in Manhattan.

In addition to conducting prayer and memorial services, CMC organized a task force to support the rescue and relief work at ground zero. CMC member Lindley Hanlon

coordinated with the City Rescue Center in Manhattan, and she and volunteers Lily Kung, Judy Chen, Linda Tao, David Ngo and John Taylor took up the task of finding, purchasing and delivering certain special pieces of equipment vital to the rescue efforts and nearly depleted from local suppliers, including

long-sleeved rubber electricians' gloves and double-cartridge respirators. Through diligent efforts the team managed to find a few pieces left in area stores, but finally had to appeal to the wider DDMBA network, which found and delivered the necessary items in shipments from Rochester, NY; Florida; and finally, from Taiwan. Our prayers go out to all the victims of September 11th, our best wishes go out to the survivors, and our heartfelt gratitude to the thousands of police officers, firefighters, emergency service workers, health care workers, spiritual leaders, volunteers and all the others who continue to work selflessly to relieve our suffering during this difficult time.

Shifu Inaugurates New Affliate

On May 15, 2001, the Meditation Group, the Chan Center's newest affiliate, sponsored a lively fundraiser at its quarters in Arpad Hall at 323 E. 82nd Street in Manhattan. The event was held to celebrate the publication of Chan Master

Sheng-yen's newest book, Hoofprint of the Ox (Oxford University Press, 2001, with Dan Stevenson), and featured Master

Sheng-yen's inaugural lecture at the Meditation Group.

More than 70 people crowded the hall to hear Shifu speak on "Zen and

Compassion", to partake of the delicious buffet provided by the well-known Manhattan vegetarian restaurant, Zen Palate, and to avail themselves of Shifu's gracious offer to sign copies of the new book.

"The Meditation Group is especially grateful that Shifu was able to add this event to his busy schedule," said Charlotte Mansfield, one of the event organizers. "His instruction is the foundation on which we build our practice."

The Meditation Group was founded last year by Chan Center board member Lindley Hanlon to meet the needs of Manhattan residents. The group meets Tuesday evenings for meditation and sponsors an ongoing program of meditation classes, Dharma talks, and related activities. For more information visit the web site at www.meditationgroup.org or call (212)

722-4728.

Shifu in Central Park

On Saturday, June 2, 2001, Master Sheng-yen addressed an outdoor gathering on the Great Hill in Central Park as part of Tricycle Magazine's "Change Your Mind Day". The annual event includes group meditations, performances, and talks by a wide variety of Buddhist leaders. Shifu's talk was immediately preceded by a chant for world peace by Kunsang Detchen Lingpa Rinpoche, bringing to mind Shifu's work for the United Nations Millennium Peace Summit last August.

Today, however, Shifu 's message was directed more specifically towards the concepts and methods of Chan practice. He explained that Chan is a simple way to express the Buddhadharma, whether it be through monastic, community or individual lives. Applications of Chan practice in daily life help us to live more safely and cooperatively.

Shifu reminded us that whether we are enjoying personal success or facing adversity, there are two points we should keep in mind. First is that the most gracious manner of conducting our interactions with other people is to place their concerns in the forefront. Secondly, when encountering problems and difficulties, we may benefit more by handling them with wisdom and compassion than by trying to escape.

Shifu recognized that in times of adversity we might prefer to escape, but we usually cannot. We therefore should consider altering our perspective by viewing an adverse situation as an opportunity for

self-improvement. He suggested that we follow four steps in dealing with a problem:

1) Face it; 2) Accept it; 3) Deal with it; 4) Put it behind you.

Shifu went on to demonstrate this approach to problem-solving by manipulating his hands as though untangling a knotted thread, patiently tugging at the knot until it broke free. He reminded us that pulling on a knotted thread in frustration only binds it more tightly, and by analogy, that working in conflict with others, and fighting against prevailing conditions will generally make matters worse. It is more fruitful to combine the principles of compassion and wisdom

-- compassion in dealing with people, and wisdom in dealing with affairs.

Buddhists in New York

Guoyuan Fa Shi was invited to be part of a panel of speakers representing

New York's diverse Buddhist communities on Wednesday, June 6, 2001, at the

Interfaith Center of New York. Buddhists make up one of New York's most diverse

religious communities, with groups coming from Bangladesh, Burma, Bhutan, China,

Cambodia, Korea, Japan, Laos, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tibet and Vietnam, as well as a

fast-growing number of Westerners. The one-day intensive seminar, called

Buddhists of New York: An Educational Program for Religious Leaders of New York

City, was designed to examine the diversity of Buddhist communities in New York

and to inform the city's religious leaders and interested public about the vibrant

Buddhist communities in their neighborhoods.

Guoyuan Fa Shi was asked to explain: first, how his particular community came

to New York; second, the spiritual and social role of the Chan and Retreat

Centers in his community; and third, his personal role as a monk in the Center and in

the community.

Guoyuan Fa Shi began his talk by telling the story of a poor farm boy who had been

given his very first banana. Having never seen a banana before, the boy brought the

exotic fruit to school to share its wonderful taste with everyone. That young

boy was Master Sheng-yen, and the story was meant to illustrate the spirit of

sharing with which Shifu, after many years of practice and intensive study, set out

to bring the benefits of Buddhism to the West.

In 1980, Master Sheng-yen established the Chan Meditation Center in Elmhurst,

Queens. After seven years of continuous hard work, the Chan Center was able to

move to a bigger location in Elmhurst. Ten years later, in 1997, Master

Sheng-yen acquired the 120-acre Retreat Center in Pine Bush, New York. The organization

started out with only a handful of Westerners from a variety of different racial

and social backgrounds, as well as some overseas Chinese. In less than 25 years,

it has expanded to become a center for people from all over the world to practice

together.

Guoyuan Fa Shi explained that the role of the Chan and Retreat Centers is to provide

places where people can come to meditate and participate in a variety of different

spiritual and social activities. Those activities include meditation classes, religious

services, and retreats for one, two, three, seven, and fourteen days. Frequent

lectures and classes are given on Buddhism and related subjects, such as vegetarian

cooking, yoga and taijiquan. The Centers also function as gathering places for many

overseas Chinese as well as English-speaking practitioners. There is an extensive

library full of Buddhist materials and publications, as well as a bookstore for all the

published works of Master Sheng-yen.

The Chan Center is also a place that provides guidance in life and practice. Anyone

interested is invited to partake in the different Buddhist and cultural celebrations

such as the Buddha's Birthday and Chinese New Year. Moreover, it serves as an

organizer and administrative contact for events such as the Gethsemani encounter,

the World Peace Summit for religious and spiritual leaders, and the dialogue between

the Dalai Lama and Master Sheng-yen in 1998. The Center is also the headquarters

for affiliated groups around the U.S. and in Europe.

Finally Guoyuan Fa Shi described his role as a monk in the Center and in the

community. He gives lectures in Buddhism, teaches meditation, guides and assists in

intensive retreats and attends interfaith dialogues. His administrative activities

include the general maintenance of both the Chan Center and the Retreat Center,

including the renovation and construction project on the 120-acre upstate facility.

Guoyuan Fa Shi concluded his talk by saying that as a monk, he uses the

principle of sharing and the attitude of offering to devote himself to the service of others.

Other activities in the seminar included educational presentations on the history

and development of Buddhist communities in the city, and a round-table discussion of

social action by Buddhists in America.

Guoyuan Fa Shi Speaks in Shawangunk

Guoyuan Fa Shi, the abbot of the Chan Meditation Center, and of its affiliated Dharma Drum Retreat Center in the Shawangunk area of New York's Hudson Valley, was invited to give a talk on Buddhism and Chan practice at the region's historical Stone Church on July 1st of this year.

The Stone Church has long been a gathering place for the area's community of

art-ists, and has recently become a center of activity for various religious and spiritual traditions. This was the first time, however, that a Buddhist monk had been invited to speak.

To an audience of more than thirty people, the moderator Maureen Radl first related the history of the Stone Church, and then introduced Guoyuan Fa Shi with a brief biography, including his reasons for becoming a monk, his experiences in Thailand, and his meditation training under Chan Master

Sheng-yen.

Guoyuan Fa Shi then opened his talk with a short biography of Sakyamuni Buddha, describing his royal birth, and his decision to leave home and give up all his worldly goods in response to the suffering he witnessed. Sakyamuni determined to seek ways to end all sufferings, and after his enlightenment, he began to share his teachings of the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path in order to help all sentient beings depart from suffering. Guoyuan Fa Shi stressed that Buddhism does not only focus on the reality of human sufferings, it is also interested in the development of human spirituality and the promotion of world peace. In

addition, Buddhism emphasizes a twofold human transformation: cultivating wisdom to eliminate vexation; and cultivating compassion to alleviate all suffering in the world.

Chan practice, according to the abbot, places less emphasis than some schools of Buddhism on philosophical principles and knowledge, and more on

direct, profound realization as the means to self-improvement. Guoyuan Fa Shi spoke of the importance of contemplating the present moment as a way of detaching from the illusion of self, and of

self-discipline as the way to release oneself from bondage. He then taught the audience a simple method for relaxing one's mind and body from head to toe, which can lead to the experience of Chan.

The afternoon concluded with a question and answer session, after which each member of the audience received a copy of A Meeting of Minds, the record of Master

Sheng-yen's historic dialogue on the wisdom teachings with His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Dharma Lecturer Training Program Enters

Sixth Term

The Dharma Lecturer Training Program at the Chan Meditation Center will enter its sixth semester when the first

class of the fall term convenes on September 21st. The program was inaugurated

in May 1999, as part of a two-pronged effort to train personnel to help the Center

spread Shifu's teachings to an ever-widening audience. The Chan Training Program

prepares meditation instructors, retreat monitors and timekeepers, with the goal

of eventually graduating students competent to conduct personal interviews and

lead retreats. The Dharma Lecturer Training Program prepares teachers to speak

on specific Dharma subjects, like the Four Noble Truths, Karma and the

Twelve-Link Chain of Conditioned

Arising, and will eventually study the great sutras that influenced the development of the Chan

school.

The first class was a small group of students invited by Shifu, but in the second

year the program was opened to all Center participants, and now functions as both a

training program for potential lecturers and as a Dharma study class for practitioners.

The format includes lectures by Shifu, short presentations in small groups, more

extended presentations to large groups, evaluations, and discussions with sangha

members. Students who hope to become lecturers must prepare a rigorous series

of lectures and are graded by their peers according to criteria developed by

Shifu, which include fluency with the subject, clarity of presentation, use of analogies

and examples drawn from personal experience, time management, and the extent to

which the lecturer projects the attitude of a friend and colleague, rather than the

superior attitude of a "teacher". Students who don't feel ready to be "put on the spot" can

join the class as auditors, and while learning the Dharma also help the

student-lecturers by functioning as audience, asking

questions when something isn't clear, and participating in follow-up discussions.

Because of the Center's need to present the Dharma to both English and

Chinese-speaking audiences, the class is divided

into separate sections conducted in English and Chinese. Both sections meet on

Friday evenings, 7:00 to 9:15, at the Chan Meditation Center, 90-56 Corona Avenue

in Elmhurst.

For more information please e-mail the Chan Center at ddmbaus@yahoo.com.

Annual Picnic Draws a Crowd

On August 6,2001, instead of the Chan Center's usual Sunday open house, approximately fifty members and friends of the Center met at Hempstead Lake Park for this year's annual summer picnic. The day began at 9:00 in the morning, when everyone met at the Center to catch the rented yellow school bus, and lasted until 4:30, when everyone got back on the bus to head back to the Center.

Guoyuan Fa Shi began the day with a short story about a monk who had been ordered by the King to carry a small bowl filled to the top with oil. The monk was forced to walk a long distance without spilling any oil to test his level of concentration. Though many distractions and obstacles were set in the monk's way, including the threat of execution if he failed, the monk proved his high level of concentration by not spilling even a single drop of oil.

Guoyuan Fa Shi asked us if we were interested in taking the same challenge. He reassured us that of course noone would be executed, but that there would be a prize for anyone who succeeded.

Everyone was handed a small white styrofoam bowl and we were sent down to the small lake to fill them with water. Then everyone

-- men, women, and children as young as three-year-old Mhaya Polacco -- began a slow procession from the lake back to the picnic tables. Though Mhaya's concentration was broken by some attractive rocks and feathers she found along the way, everyone else carefully carried their bowls full of water in two hands, staring down and concentrating on not spilling a single drop, just as the monk had done long ago.

Halfway back to the tables some of the kids noticed a young black crow sitting in the grass and carried her back to the picnic area. Guoyuan Fa Shi blessed her, and the kids found a safe tree in which to leave her, just as the others arrived with their bowls full of water. Everyone received a prize of dried herbs for their efforts at mindfulness, and it was time for lunch.

There was so much different food to eat it would have been impossible, if not dangerous, to taste it all. There were sushi rolls, barbecued corn, vegetarian ham sandwiches, red bean rolls, Chinese noodles with mushrooms, macaroni and potato salad, croissants, rice cakes, fruit salad, watermelons, chips, cookies and much more.

After lunch everyone participated in a question and answer game about various aspects of Buddhism

--what are the four noble truths? the five skhandas? Shifu's birth year? Whoever answered correctly won a prize

-- stuffed animals for kids, or Shifu's latest book, Hoofprints of the Ox, for those old enough to read it. After the quiz there were more traditional picnic games

-- musical chairs, charades, water-balloon toss, and the number seven game, where everyone stands in a big circle counting, and must clap at any number having to do with the number seven (7,17,128).

When the organized games were completed, there was still time to relax, play volleyball, and enjoy the beauty of the park. Guoyuan Fa Shi tested his skills riding a "Razor" scooter borrowed from one of the kids, gliding downhill with perfect balance and poise.

At exactly 4:00 the bus appeared, signaling that it was time to clean the picnic tables, pack everything away, and head for home, after a

fun-filled day had by all.

In Brief …

Tuesday sitting group revived

The Tuesday evening meditation program at the Chan Meditation Center was

inaugurated back in the early days of Shifu's teaching career in the U.S. In the fall of

1998, the program was terminated, due to a number of factors that had caused a

drop in attendance. Many of the participants were attending Shifu's Wednesday

evening class on Shantideva's Bodhicharyavatara (Entering into the Way of the

Bodhisattva), and were unable to come to the Center two evenings in a row; it was

also a time when the Center was going through a phase of expansion and was

very shorthanded, and therefore unable to arrange for a consistent timekeeper.

In the spring of this year, however, Guoyuan Fa Shi decided that the program was a valuable one and should be revived. A regular member who lives near the Center volunteered to serve as the timekeeper, and the first sitting was held on July 10.

The group meets every Tuesday evening with the following schedule: Opening prostrations at 7pm; thirty minutes of sitting meditation; ten minutes of yoga; another thirty minutes of sitting; twenty minutes of walking meditation. A

thirty-minute period of reading and discussion has been added to the program, with topics currently being chosen from Master

Sheng-yen's book, Zen Wisdom. Participants then chant the Heart Sutra before winding up with closing prostrations at 9pm.

Attendance has been good so far, and on July 31 the group moved from the small Chan Hall on the second floor to the main Buddha Hall, making room for many more meditators. It is hoped that the program will benefit even more people in the future.

Fourteen-day Huatou Retreat

A fourteen-day huatou retreat was held between June 20 - July 4, 2001, at the