| |

Fall 2000

Fall 2000

Volume 20, Number 4

|

Four Tranquilities:

Making

the mind tranquil: To lead a content life with few desires.

Making the body tranquil: To lead a diligent life with frugality.

Making the family tranquil: To foster mutual love and assistance in family.

Making actions tranquil: To cultivate purity and vigor of mind, speech and action.

Chan Master Sheng-yen

|

|

Song of Mind of Niu-t'ou Fa-jung

Commentary by Master Sheng-yen on a

seventh-century poem expressing the Chan understanding of mind. This

article is the 30th from a series of lectures given during retreats at the

Chan Center in Elmhurst, New York. These talks were given on December 1st and

26th, 1987 and were edited by Chris Marano. |

Commentary by Master Sheng-yen |

| The Four Noble

Truths

This is the third of four Sunday afternoon talks by Master

Sheng-yen on the Four

Noble Truths, at the Chan Meditation Center from November 1st to November 22nd,

1998. The talks were translated live by Ven. Guo-gu Shi, transcribed from tape by

Bruce Rickenbacher, and edited by Ernest Heau, with assistance from Lindley Hanlon. Endnotes were added by Ernest

Heau. |

A Lecture by Master Sheng-yen |

|

The Swastika

This is the second part of a two-part article on the symbolic meanings of the swastika in world culture and the Buddhist religion. |

By Lawrence Waldron |

|

Speech at The Millennium World Peace Summit of Religious and Spiritual

Leaders Transcription of the speech given by Shifu at the World Peace Summit which took place at the

United Nations on the 29th of August, 2000. |

Master Sheng-yen |

| Environmental Protection

Transcription of a speech given by Shifu at the Waldorf Astoria on the topic of religious

perspectives on environmental protection. |

Master Sheng-yen |

|

News |

|

This magazine is published quarterly by the Institute of Chung-Hwa Buddhist Culture, Chan

Meditation Center, 90-56 Corona Avenue, Elmhurst, New York 11373, (718) 592-6593. This is a non-profit

venture solely supported by contributions from members of the Chan Center and the readership.Donations for magazine publication costs or other Chan Center functions may be sent to the

above address and will be gratefully appreciated. Your donation is tax deductible.

ęChan Meditation Center

Dharma Drum Publications:

Phone: 718-592-0915

email: dharmadrm@aol.com

homepage: http://www.chan1.org

Address: 90-56 Corona Ave., Elmhurst, New York 11373

Chan Center phone, for information and registration for programs: 718-592-6593

Founder/Teacher: Shi-fu (Master) Venerable Dr. Sheng-yen

Editors: David Berman, Ernest Heau, Harry Miller, Linda Peer

Managing Editor: Lawrence Waldron

Section Editors: David Berman: practitioners' articles, interviews, etc.

Buffe Laffey: news and upcoming events

Design: Guo-huan / Lawrence Waldron

Copy Editor: John Anello

Other assistance: Nora Ling-yun Shih, Christine Tong

Song of Mind of Niu-t'ou Fa-jung

Commentary by Master Sheng-yen

This article is the 30th from a series of lectures

given during retreats at the Chan Center in Elmhurst, New York. These talks

were given on December 1st and 26th, 1987 and were edited by Chris Marano.

Use mind to stop activity

And it becomes even more erratic.

The ten-thousand dharmas are everywhere, yet there is only one

door.

It is important that we understand and accept the advice given by the first two lines of the verse: "Use mind to

stop activity and it becomes even more erratic." If you use the mind to seek enlightenment, it will only become more

confused. If you use the mind to stop vexations and wandering thoughts, it will also become more confused. You will

be unable to develop any power in your practice.

There is no question that the ultimate goal of practice is to gain enlightenment. There is also no question that the

purpose of all methods is to stop the mind from moving. It does not seem to make sense. It seems that I

am contradicting myself. First I say that seeking enlightenment or trying to stop the mind will only cause confusion,

and then I say that the goals of practice are to stop the mind and attain enlightenment. How can Chan claim to be clear

and direct and yet be so confusing?

People who have been practicing for a while know that there is a good explanation. Simply, before we begin to

practice, we know the purpose of meditation; but when we begin to meditate, all ideas and goals are put down. All you

should concern yourself with is the method. Your mind is on the present moment, and not comparing experiences to the past

or speculating about the future. Yet, this is a big obstacle for many people. They cannot help but use their minds to

prevent thoughts from arising, and then they get frustrated when it does not work.

The Chinese have many sayings to describe such confusion and misdirected intention. One saying describes an

impatient farmer who pulls on rice stalks to make them grow faster. The result: In his impatience, he uproots the plant before

its time and loses the crop altogether. Another saying speaks of the man who puts one head on top of another in order

to keep the first one in line. In this case, two heads are definitely not better than one. Another maxim speaks of trying

to stop water from boiling by pouring hot water into the pot.

The theme that runs through these three sayings is similar: meddling and misdirected intention only serves to

complicate problems. When it comes to stopping wandering thoughts, we must first remember that mind is an illusion, albeit

a deeply rooted one. It is this mind of illusion that we must use in order to transcend the mind of illusion. It is a

tricky business. If you try to use your mind to stop your mind from moving, it will not work. On the other hand, if you

allow your mind to stop moving, it will happen. Every time

you try to force your mind to do your bidding, you only serve to create

another "head" with which you must contend. If you seek enlightenment

in such a manner, you are walking down the wrong path.

Using the mind of vexation to help or cure the mind of vexation does

not work. Yet, people try all the time. In fact, psychologists and other

therapists make good money attempting to do so. I am not saying that psychological

counseling is useless, but its success is usually temporary. The best it can do

is to replace or cover one illusion with another. It is like trying to stop

water from boiling with more hot water. The best thing to do would be to put out

the fire below the pot. Chan methods are devised to help one transcend the

mind of vexation. The strategy is simple: practitioners are directed to place

all energy on the method and disregard the mind altogether. The mind is illusory,

so there is nothing to worry about. You may not solve your problems, but with meditation, your mind will become clearer and more stable. You will begin

to recognize yourself better — your moods, your patterns, the way your thought process works — and in so doing

you may eventually discover that your so-called problems have disappeared.

Chan methods seem easy and direct, yet I notice that there are far fewer Chan teachers than there are psychologists. I also hear phychologists

make a lot of money. Maybe I am in the wrong business. Or, perhaps I should

pretend to be a psychologist and teach people Chan Method. [laughter] At one

time, I did a series of radio shows in New York, and at the end of each show,

people would call in with questions. My advice seemed to be useful, but the

truth is, none of the answers came from me. I just passed along information that

I received from Chan masters of the past. You are probably thinking, "It's

easier to be a Chan master than it is to be a Chan student. Students must work

hard all the time, but all masters have to do is quote words of the Buddha and

past patriarchs." Well, if I ever shift careers and become a therapist,

maybe you can take my place as a Chan teacher. In the meantime, it would be best

to stick to your method and continue to work hard.

In our practice, we do not want our minds to be moved by the environment,

whether the thought or feeling is pleasant or unpleasant. Most people are in no

hurry to ignore pleasant states of mind. They perceive them to be a beneficial

result of practice and attempt to hold on to them. I am sure this has happened

to all of you. You will

notice, however, that the pleasant condition will slip away as soon as you begin to cling to it. Usually, what follows

then is a feeling of regret, and then a search for a series of steps that will bring you back to that feeling. Before you know

it, you are lost in a tangle of wandering thoughts, which leads one to feel frustrated, angry, depressed or

self-doubting. After a few moments, minutes, or hours of this, you become fed up and yell, "Stop it!" That technique, however,

does not work. The only thing that works is allowing your mind to return to the method to begin anew.

Telling yourself, "Don't think, don't think!" does not work. Working hard on the method does, but working hard

does not mean tensing every muscle, constricting the brain and expending enormous amounts of energy wrapping your

mind around the method. I always say, "Relax your body, relax your mind, and work hard." It is not contradictory.

Relaxation is extremely important. If you are tense or are expending a lot of energy, you will eventually run out of energy,

become fatigued, and be open to a new flood of wandering thoughts. Working hard means patiently and persistently staying

on the method, and immediately returning to the method if you find that you have left it. It takes vigilance and will power,

but it does not require excessive energy.

When meditating, you should also not be concerned with what you may have experienced previously. If you

experienced something pleasant, even a period of clarity, do not try to repeat steps that you think got you there. If you

experienced something unpleasant, do not try to avoid what you think placed you in that position. The past is gone. The future

has not arrived. All you have is the present moment, which can never be the same as any other moments from the past

or future. Therefore, it is pointless to return to what you think was a favorable state of mind. You are different, the

environment is different, the moment is different, everything is different. Even if you experience something similar to what

you experienced earlier, it is not the same, and is a product of new, interacting causes and conditions. Every moment,

your mind should reaffirm the present moment, and the way to do this is to remain on your method of practice. Any

thoughts of the past or future will only cause you to stir up more wandering thoughts.

The next two lines: "The ten-thousand dharmas are everywhere, yet there is only one door." Most practitioners wish

to feel that they are progressing in their practice. They want to know if

they can move on to a new, different, or better method of practice. Perhaps they think that a method contains a certain amount of benefit, and once it is used up, it

can be discarded in favor of a new and better method. It reminds me of the person who stands at the top of a beautiful

mountain in the distance, and wishing he or she were there instead. Someone else may tell you, "Mountains in the distance

will always seem better than the one on which you are standing. This mountain is as beautiful as any other." No

matter. Off you go, running down one mountain and scaling another. At the top, you feel temporarily satisfied, but, again,

off in the distance are even taller mountains. So off you go again, thinking the next one will be the best and last

one, because it looked so beautiful from the previous mountain top; and when you arrive, you realize that it is cold,

windy, devoid of life and vegetation. There is nothing to drink and eat, and you are cold, hungry and thirsty.

Practitioners can often be like a frustrated mountain climber. They think that the method they currently use is

inferior and cannot wait to try another. People who count their breaths wish to work on a

hua-t'ou; people reciting

mantras wish to practice silent illumination; people working on one hua-t'ou feel that another one might be better.

Once, while lecturing in Iowa, I mentioned that the method for early Chan masters was no method, and that, for those

who are ready, no method is the best method. At the end of the lecture, a man approached me and said, "I agree with

you that no method is the best method. Would you teach me the "no method" so I can use it?" People

never cease to amaze me.

The best approach is to choose one method and stick with it. Derive as much flavor from it as you can. In

switching from one method to another all the time, you will never penetrate any of them deeply enough to derive good

benefits. Stay with one method and get to the heart of it.

Several people on this retreat who are using the method of counting breaths are anxious to move on to a hua-t'ou

or silent illumination. For some reason, they feel that counting breaths is a basic, introductory method, whereas

hua-t'ou and silent illumination are advanced methods. There are many paths to the experience of no-self, and counting breaths

is one of them. It can take you to enlightenment, but that should not be your concern. If, instead of concentrating on

your method, you are wondering why you are using one method and not another, then you are not in a position to be

requesting advanced meditation methods.

If you truly concentrate on counting breaths, the method will eventually disappear. At that point, your method

will naturally change to silent illumination. Therefore, do not worry that you may be missing out on something because

you are counting your breaths. Besides, there are many variations of and approaches to counting breaths. As people continue

to practice, they discover that their understanding of the method and of their minds changes, or evolves. This is one

of the qualities of a good, vital meditation method. If you feel that your method has become stale, come to me and I

will help you. The truth is, methods cannot become stale, but people can.

If you are having recognizable problems with your method, I consider it a sign of progress. It means that you are

working. I am more worried about the people who never seem to have problems. Such people sit on their cushions in a

happy fog and think it is a clear, enlightened state of mind. Whenever I ask them how they are doing, they look at me with

a dreamy smile and say, "Fine." That concerns me. Other people say, "I don't know. I'm not sure if I'm practicing right

or not." When I ask them how they are using the method, they respond, "Oh, the way you taught me." I am not a

mind reader. I cannot help people if they cannot tell me what they are experiencing. If you have problems or concerns

about your practice and you want my help, you must at least meet me half way. Come with specific questions that I can

address.

Most of all, do not be lured by stagnant states of mind where nothing is happening and everything seems to be okay.

For instance, someone yesterday told me that every time she

meditates, she reaches a point where wandering thoughts invade her mind and it disrupts her concentration. It happens

at the same point every time. She decided that such an occurrence must be a normal phenomenon and was content

to experience it over and over again. Yes, it is normal for wandering thoughts to arise when you practice, but when

the same thing happens every time at the same point in your practice, then there is a problem that needs to be

investigated. At least this woman was able to recognize it and come to me for guidance. I would not have known otherwise.

Her problem reminds me of a story when I was younger and in the army. One of the men was designated to go out

every morning to buy food for the troops. With an empty sack slung over his shoulder, he would head out before dawn

and walk down the road to get the food. One morning, he decided to take a short-cut through a cemetery. He walked

and walked for quite some time, and he began to wonder if this were a short-cut after all. Still, he walked and

walked, passing gravestone after gravestone, and dawn arrived and it became light enough for him to see. It was only then

that he realized he had been walking in circles around the cemetery. I hope none of you are turning in circles inside

your mind. If so, you already know the solution to your problem. Return to the method and leave your mind alone.

The Four Noble Truths

by Master Sheng-yen

This is the third of four Sunday afternoon talks by Master

Sheng-yen on the Four Noble Truths, at the Chan Meditation Center, New York,

between November 1 and November 22, 1998. The talks were translated live by Ven.

Guo-gu Shi, transcribed from tape by Bruce Rickenbacher, and edited by Ernest

Heau, with assistance from Lindley Hanlon. Endnotes were added by Ernest Heau.

Please

click here for the article

The Swastika (Part 2 of 2)

by Lawrence Waldron

Lawrence Waldron is an Adjunct Professor of Fine Arts and Art History at St. John's University in Jamaica, New York. He holds

an MFA from School of Visual Arts, New York City.

This is the second part of a two-part article on the symbolic meanings of the swastika in world culture and the Buddhist religion.

The Buddhist Swastika

In one scene from the Lankavatara Sutra, the Buddha is intriguingly described as "laughing loudly" and vigorously "like a king

of lions" whilst "Emitting rays of light from the tuft of hair between the eyebrows, from the ribs, from the loins, from the

Srivatsa on the breast and from every pore of the skin," light which "shone like the flames at the end of a kalpa". Except for the unusual

description of the Buddha roaring with laughter, these are somewhat typical attributes of the Buddha in Mahayana literature. The emission of bodily

light and the circle of hair between the eyebrows, as well as the characteristic "vigor like an elephant" (as described in the

Buddha Karita of Asvaghosa) are among these `Signs of a Buddha'. The "srivatsa" on the Buddha's breast is the swastika, by a less

common name, and numbers among these 132 signs.

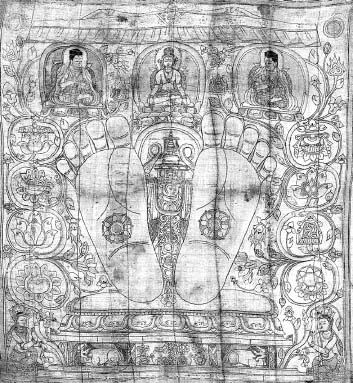

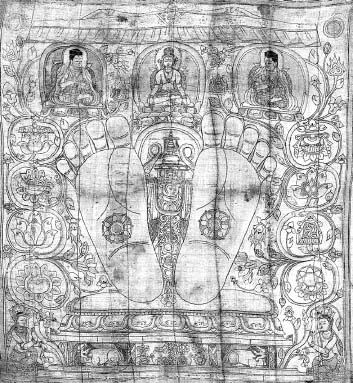

|

|

|

Figure 6 |

The Swastika on the Buddha's Chest

Only Buddhas and their highest disciples are ever adorned with the swastika, so in Buddhist art, the symbol can be taken as a

mark of spiritual achievement. The placement of the swastika, dead center on the Buddha's breast is also quite significant and is a

popular image seen, even today, in Tibetan and Chinese Buddhist images (see Figure 6).

In such an image, the swastika is as much a focal point as the Buddha himself. In fact, the symbol becomes loaded with

profound and subtle meanings, marking `the heart of' the Buddha like the `X' on a treasure map. One might then ask the question: "What

is at the heart of the Buddha?" Various Buddhist schools of thought would rush to answer this question. Indeed, the question

necessarily references the deepest, most engaging

Buddhist philosophies. Tathagatagarbha theory figures highly among these possible

keys to the "heart of the Buddha".

In the Vijnanavadin theory of Tathagatagarbha, or "womb of the Thus Gone Ones", all buddhas in all the worlds and galaxies

originate from the clear, essential womb or storehouse of Mind. The Tathagatagarbha is the clear, luminous, undifferentiated essence

of buddha nature. It is the source of all buddhas and is at the core of any one

buddha, including the historical Buddha of our world, Shakyamuni. It is extant not only in buddhas but at the core of all

beings, regardless of the circumstances or conditions to which they are born. It is because great spiritual beings achieve union with

this transcendent core of Buddha Mind that

they are called `buddha' per se and the rest of us are not. It is a matter of attaining a

seamless confluence with this Tathagatagarbha that earns one the lofty title, but to the entitled, "buddha" is just a word. All beings

are buddhas, though presently clouded from their own buddha nature by ignorance, desire and aversion.

Another school of Buddhist philosophy has a divergent, if not opposing view of what lies at the crux of the Buddha.

Nagarjuna's Madyamaka school also believes that we are all buddhas without truly knowing it. But the Madyamaka school posits that

sunyata, or emptiness, is the core of the Buddha and indeed of all things. For the

Madyamaka, all things are contingent upon other things

(dependent origination) and are therefore "empty" of self nature. If nothing is self-existent then there is no place for us to hang

our philosophical hats in existence. Even the profoundest truths held by other religions and even other Buddhist philosophical

schools are devoid of concrete truth. Even the philosophy of the Madyamaka itself is believed by Madyamakans not to be an ultimate,

unchanging truth. If it were concretely true, it would refute itself. If it refuted itself, it could not be true. Arguments against

the Madyamaka position are likewise devoid of ultimate truth. This is why Nagarjuna resorted to no `theory' of existence in favor of

a completely empirical approach to life. Life is experienced only directly, through observation, through the unbiased clarity of

meditation and action is taken directly upon these observations and insights, not from any theoretical position. "Luminous,

unspoiled buddha nature," or Tathagatagarbha would seem too much like a theory of concreteness to students of the

Madyamaka.

In its position at the center of the Buddha's body, the swastika can reference either of these philosophies. The meaning ascribed

to the symbol depends on the denomination of the artist drawing it and, and of course, the requirements of his patron.

If the swastika, at the center of the Buddha's chest, symbolically represents the pure empirical sunyata or the eternal,

profound Tathagatgarbha, what might the swastika's visual characteristics mean? After all, it may symbolize indescribable states of mind

but as a symbol, it does have a physical presence, with shape, line and even color.

Firstly, four cardinal spokes (the arms of the swastika) sprout from a central axis. The importance of direction in Buddhist

diagrams (yantras and mandalas) cannot be emphasized

enough. The swastika has directional and even barometric meanings in many of the cultures where it occurs. In Buddhism,

certain deities, colors, minerals and implements are associated with certain cardinal directions of east, west, north and south, and zenith

and nadir too. Certain emotions, virtues and vices are also associated with the cardinal directions and so a cardinal figure like the

swastika is rich with graphic and symbolic possibilities for Buddhist artists.

|

|

|

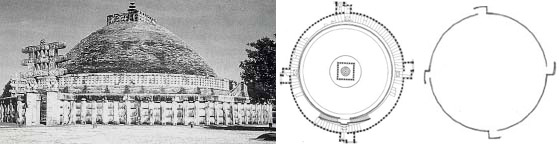

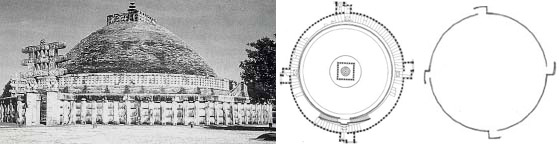

Figure 7 |

The symbol often functions as a marker, implying philosophical meanings purely because of its position. But just for the purpose

of marking a significant spot, a dot (urna) or a swirl (like on the Buddha's forehead) would have sufficed? Why not a Dharma

Wheel (Dharmachakra) as is commonly depicted in the palms and on the foot soles of the World Honored One?

( see Figure 7 ). Therefore, we must ask whether the visual characteristics of the

swastika itself are significant in some way of the Buddhist ethos.

The Swastika in the Buddha's Hand

Swastika shapes and designs abound in Buddhist architecture, sculpture, painting and

jewelry. The symbol doesn't necessarily mean the same thing in every context, but what is obvious

at once is that the swastika is a four-armed figure with an additional four perpendicular

extensions. The numerological implications are many, most of these stemming from the significance, in

Buddhism, of the numbers 4 and 8.

The most obvious association with the number 4 is that of the Four Noble Truths (Suffering,

the Root of Suffering, the Possibility of Ending Suffering and The Path that Ends Suffering).

The Four Noble Truths are a meaning we can assume to be commonly implied in all images of

the Buddha in seated meditation or in a posture of teaching. But there are other possible references

to the number 4 that might co-exist with the Four Noble Truths. If the Buddha is seen in the

enlightenment posture, his right hand in bhumisparsha mudra ("earth-touching" hand gesture),

the swastika on his chest referencing the number 4, both the Four Noble Truths and The Four Merits/Fruits would be implied. The

Four Merits are becoming a Stream Entrant, becoming a Once Returner, becoming a

Non-Returner, and attaining Arhatship. The

Buddha would embody all these stages of spiritual achievement, the culmination of which is his Nirvana. The Buddha in a

teaching gesture involving a swastika, his hands in Dharmachakra mudra ("Dharma-Wheel Turning" hand gesture) would represent the

Four Fearlessnesses of a Buddha, especially if he is surrounded by disciples. The Four Fearlessnesses have to do with proclaiming

truths to students of Dharma and are: to fearlessly Proclaim All Truth; fearlessly Proclaim the Truth of Perfection/Faultlessness;

fearlessly Expose Obstacles to Truth; fearlessly Proclaim the Way to End All Suffering.

|

|

|

Figure 8 |

In its four-pronged aspect, the swastika would also make references to The Four Foundations of Mindfulness, The Four Great

Vows of a Bodhisattva, The Four classes of Buddhist Disciples and The Four Holy States. The symbol may mean any of these

things when adorning a senior disciple of the Buddha. The mahasattva,

Avalokiteshvara, is often depicted holding the emblem among

many others in his one thousand hands (see Figure 8). In such a case, Avalokiteshvara can be understood as teaching the

four-fold Dharmas (Four Noble Truths etc.) in the Buddha's stead, possessing the accomplishments

of a buddha as are symbolized by a swastika, or simply conferring long life upon his devotees.

The Swastika in Buddhist Architecture

The swastika functions as more than a superstitious or decorative element on the edges of sand mandalas and along the lintels

of Buddhist temples. The symbol carries deep philosophical and historical clues on Buddhist thought in its architectural context.

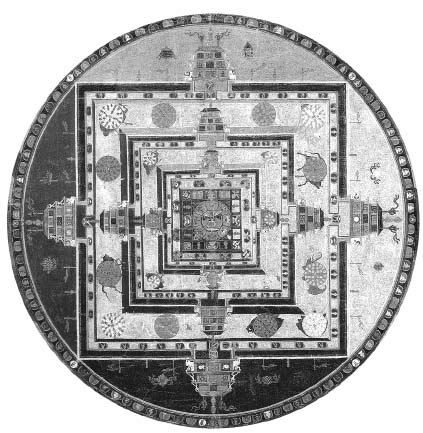

The number four again figures more highly than any other in the configuration of Buddhist mandalas and

monumental

structures (stupas).

The mandala is a symmetrical, psycho-architectural model of the quest for enlightenment. Imagined in 3 dimensions from its

more common 2-dimensional depictions in colored sand or paint, the center of the mandala is seen as the pinnacle of spiritual

achievement. This central area of the architectural layout is represented in mandala art as a sort of palace with four gates. The

graduated outer (or lower) levels of the mandala are rungs of lower spiritual accomplishment leading up to the `palace of enlightenment' at

the center-top of the diagram. Stupas are the three-dimensional cousins of

mandalas, used as monuments to the Buddha's life on

earth. They usually contain some relic of the Buddha. Both stupas and mandalas have four symbolic gates in the four cardinal

directions. This gives their floor plan the appearance of a square with four protruding openings or a cross (see Figure 9).

|

|

|

Figure 9 |

These elaborate gates (especially in the case of stupas) are meant to be entered

by Buddhist practitioners entering from the left on their clockwise

circumambulations around the structure. Therefore, they usually open towards the right,

perpendicular to the actual entryway of the structure. This right-angled turn in the entryway can

be seen in the floor plan of Sanchi stupa in Northern India, one of the oldest

monuments to the life of the Buddha (see Figure 9). Observe that the right-angled gateways

by themselves form a swastika. This is no accident. A monument this old

definitely shows pre-Buddhist and even pre-Hindu influences in its orientation to the sun

and its use of the swastika (a sun symbol)

as the key to its structure. Even the Buddhist tradition of clockwise devotional

circumambulation, observed strictly at Sanchi Stupa

to this day, copies the sun's seeming clockwise path across the sky. The old pagan sun-symbol swastika thus reasserts itself

on many

levels at Sanchi Stupa, a Buddhist monument.

The Number Eight

Any associations the swastika might have with the number 8 would be most likely subsumed by the more common use of the

eight-spoked Dharma wheel. The Dharmachakra is favored for almost all symbolic treatments of the number 8. The Eight-fold Path,

for instance, is almost always represented in Buddhist images by a wheel symbol either in the Buddha's preaching hand or somewhere in his immediate surroundings. The Dharma wheel is an even more common symbol in Buddhism than the swastika and for

many years after the Buddha's parinirvana, was the only way the Buddha himself was represented. It is therefore, not necessary to discuss the swastika in any depth as a numerological symbol for the Eight

fold Path, especially since the Four Noble Truths, which

are represented by the swastika include the Eightfold Path. However, it

is possible to extract the meaning of the Eightfold Path from a preaching image of the Buddha in which no Dharma wheel is

featured but only a swastika in the Jina's hand or on his chest.

The Number Five

An unlikely number can be appreciated in the configuration of the swastika, the number five. The swastika has four

cardinal branches corresponding to north, east, south and west. Many Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists begin their daily meditations

or longer prayers, not just with a salutation to the Three Jewels but with an invocation of the buddhas "in the Ten Directions,

Past Present and Future".

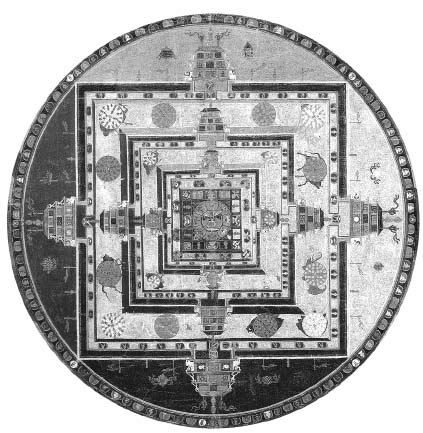

A buddha of great significance is ascribed to each of the cardinal directions with a fifth buddha at the center of the Buddhist

universe. These five buddhas represent the Five Primordial Buddhas, the Five Great Families of buddhas or the five symbolic

prototypes of buddhas. (See Figure 11)

|

|

|

Figure 10 |

Conclusion

As Westerners, we may question the necessity of employing this `double-edged' symbol in our practice and our devotional art.

We may choose to never use it again in deference to the heinous events that took place, supposedly under its auspices in the early part

of the twentieth century. However, we cannot ignore that the symbol is still in popular usage throughout a great part of the

Buddhist world and that we will continue to have to deal with it. As Buddhists, we are among a handful of peaceful, law-abiding

Westerners who have some measure of positive associations for the symbol. Are we content to leave it so or should we effect a change in

how the Western world sees this symbol? We can be sure that the swastika will keep popping up, sometimes embarassingly so, on

Buddhist statues from China and Japan in museums, antique shops and reprinted sutras and pamphlets. We are perhaps best advised

to get the issue in the open, rather than leave the non-Buddhist West's discovery of Buddhists using swastikas to chance,

misinterpretation and rumor. It is fairly certain that only one society in the whole history of the human race ever gave negative meanings to

this sacred symbol. It is left to be seen whether the powerful, millennia-old swastika is so worthy as to be reclaimed, not just by

Buddhists but by the world.

References

-

Buddhist Mahayana

Texts edited by E. B. Cowell, Dover, 1989.

-

The Buddhist Tradition edited by W. T. de

Bary, Modern Library, 1972.

-

Mandala: the Architecture of

Enlightenment by Denise Patry Leidy and Robert

Thurman, Asia Society Galleries/Tibet House, 1996.

-

Psycho-cosmic Symbolism of the Buddhist

Stupa by Lama Anagarika Govinda, Dharma Publishing, 1976.

-

The Swastika: Symbol Beyond

Redemption? by Steven Heller and Jeff Roth, Allworth

Press, 2000.

-

The Lankavatara Sutra by D.T. Suzuki, SMC Publishing, 1991.

Speech at The Millennium World Peace Summit of Religious and Spiritual

Leaders

by Master Sheng-yen

This is a transcription of the speech given by Shi-fu at the World Peace Summit which took place at the United Nations on the 29th of August, 2000. The

purpose of the Summit was to forge a cooperative effort among world religions towards acheiving peace, improving the state of the environment and helping end

world poverty. Over 1,000 religious leaders were in attendance at the Summit.

Please

click here for the article

Environmental Protection

by Master Sheng-yen

This is a transcription of a speech given by Shi-fu at the Waldorf Astoria on the topic of environmental protection from a religous perspective. One leader from

each major world religion was chosen to speak on this topic as part of the World Peace Summit, hosted by the United Nations.

Please

click here for the article

NEWS

Zen Camp 2000 at DDRC

by Lindley Hanlon

Forty children and thirty adults attended Zen Camp 2000 at Dharma Drum Retreat Center from August 18th

to 20th, 2000. The weekend was focused on family dynamics and harmony in a well-planned series of

enjoyable educational activities. Guo-yuan Fa Shi presided over the weekend's activities, leading morning and

evening services, exercises and meditation, a water carrier meditation, the family circle meditation, the campfire,

and midday offerings. Sylvie Sung coordinated all the arrangements for the weekend, oversaw a large team or

twenty- four volunteers, and assisted Yan Pei in the adult activities. The Parent Coordinator was Agnes

Wu, Youth Coordinator Jane Chen, and Assistant Youth Coordinator Joyce Li.

Under the direction of Lindley Hanlon, leader of the Buddhist Youth Group, the teen campers engaged

in: meditation classes, walking meditation, a group family drama competition, a silent contemplation nature

walk, and a natural treasure hunt for craft materials. At the rotating craft workshops they made Zen

Fountains, beaded jewelry, hand-painted T-shirts, and pasta pictures. In these activities she was ably assisted by:

Rebecca Li and David Slaymaker, as well as Joyce Li, Jane Chen, and Guo-zhen. Group Leaders were

David Slaymaker, Tan May Wong, Joyce Li, Jane Chen and Carol Yuen, assisted by Counselors Annie Ho,

Robert Yuen, Andy Ni, Cheung Li and BaiRen Wong.

Meanwhile the parents were led by Yang Pei (visiting psychologist and instructor from Taiwan) in creative workshops and dramas focused

on understanding the complexities of parental roles and family relationships. Campers and parents reunited

for the lake-side picnic lunch, drama competition, campfire, family meeting workshop, group sharing,

family circle meditation, meals and final sharing session. Winner of the Drama Competition was the play

"Stanley Family Show," written by Joyce Li's teen group and featuring an hilarious send-up of a TV game show

performed by Stanley Fang.

The warm feelings, communication, and sense of community fostered by these events were evident

throughout the weekend. The cool weather and beautiful environment of the Retreat Center were an ideal setting for

the camp. We look forward to the completion of the Retreat Center facilities during the year.

Dharma seeds growing in the West

Master Sheng-yen is pleased to announce that he has granted Mr. Gilbert Gutierrez of California, and Dr.

Max Kalin of Switzerland to organize practice groups, teach meditation, give Dharma lectures, and lead retreats.

This brings to three the number of Western lay disciples granted permission to teach Chan, by Master

Sheng-yen. Dr. John Crook of Wales, England, has already enjoyed this distinction for several years.

Three-Day Retreat

Thirty three practitioners attended the Three-Day Retreat from September 1st to

4th, 2000. Several of them were first timers attending this type of intensive

retreat. Guo-yuan Fa Shi lead all practioners through a poetic concentration

practice: practitioners carried bowls and gathered water at the nearby lake.

Slowly, they brought the water back to the Chan Hall in walking meditation. The

bowls of water were then arranged on the altar and offered to the Buddha.

Passing away of Heng-yen Shi

With deep sadness, we announce that Heng-yen Shi (former CMC member Avy Wu-Kennedy) passed away

in an unfortunate car accident on August 11th, 2000. Heng-yen Shi was the mother of

Guo-gu, former

director of Dharma Drum Publications and Chan Magazine.

Shi-fu speaks at the UN Millennium Peace Summit of Religious and Spiritual Leaders

By Carolyn Hansen

With the objective of furthering world peace, over 1,000 leaders of the earth's religions and spiritual

practices gathered from August 28th to 31st in the first UN Summit of Religious and Spiritual Leaders. The

United Nations and the gathering were first called by the drumming of the Shumei Taiko Ensemble, and then blessed

by prayers from various Native peoples and representatives of many organized faiths during the

opening ceremony on August 28th. It was hoped the sacred space created would benefit the Millennium Summit

of Heads of State scheduled to gather here the following week.

The leaders wore colorful and diverse gowns, robes or religious attire from Africa, Asia, the Americas,

Europe, the Middle East, India and the homelands of various Native people. The thoughtfulness and

reverence they demonstrated became a powerful backdrop for the conference.

On August 29th, Shi-fu was a keynote speaker in the UN General Assembly Hall. He proposed to

those gathered at the UN that "If you find that the doctrines of your faith contain something that is intolerant of

the other groups, or in contradiction with the promotion of world peace, that you should make new

interpretations of these relevant doctrines... Because every wholesome religion should get along peacefully with other

groups so that it can step by step influence humankind on earth to stay far away from the causes of war." His

speech is feathered in this issue. Other speakers that day included Goenka; leaders of the Tibetan Schools; the

Shinto High Priest, the Most Reverend Kuni Kuniaki; leaders of the Jainist; Zoroastrian; Hindu; Christian;

Jewish; Muslim; and Native faiths; Jane Goodall; as well as Secretary General of the UN, Kofi

Annan;

Maurice Strong, Chair of the International Advisory Board of the Millennium World Peace Summit, Chair of the

Earth Charter Council and organizer of the 1992 Earth Summit; and Ted Turner, founder of CNN and sponsor of

the Summit.

The following two days were spent in plenary sessions or working groups at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel.

The working groups focused on Conflict Transformation, Poverty, the Environment, and Reconciliation and

Forgiveness. Ven. Sheng-yen also was a main speaker in one of the workshop sessions on the environment.

Shi-fu and his delegation were also invited to the Thomas Berry Award dinner. Father Thomas Berry

wrote Dreams of the Earth and spoke at the banquet, which honored Tu

Weiming, a friend of Shi-fu's and

professor of Chinese history, philosophy and Confucian studies at Harvard. The Dharma Drum Mountain

Buddhist Association sponsored the closing reception on the 31st. During the conference Shi-fu was invited to serve

on the advisory committee that will plan the mechanism to connect the UN Secretary General to spiritual

leaders in areas of conflict. It is intended that this will allow the spiritual leaders to help the UN further world

peace.

Back

|

|

Fall 2000

Fall 2000