"The Importance of Repentance in Chan Practice"

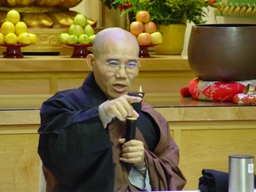

Talk presented by Venerable Guo Xing

Report written by Chang Jie 12/20/2009

On Sunday, December 20, 2009, Venerable Guo Xing, Abbot of CMC and DDRC gave a talk on "The Importance of Repentance in Chan Practice."

On Sunday, December 20, 2009, Venerable Guo Xing, Abbot of CMC and DDRC gave a talk on "The Importance of Repentance in Chan Practice."

While repentance in the West is often related to sin, repentance in the Buddhist tradition is quite different. According to Buddhism, our original nature is the same as the Buddha's-we all have the same wisdom and merit as the Buddha and the same potential to become Buddhas, but because of our ignorance, our wisdom cannot be revealed.

According to many Western religions, when people do misdeeds, it is believed that they will be punished. According to Buddhism, however, committing a misdeed does not necessarily mean you will be punished by some external force. Rather, when you commit a misdeed, a sense of having done something wrong will arise within you. Venerable gave a couple of examples to illustrate his point. For example, when you kill someone, you will feel afraid, perhaps that someone will avenge you. This fear is your own reaction to something you have done. In a way, you yourself give rise to this fear, and your actions will follow a certain pattern that will lead to consequences. Repentance will alleviate this course.

Another example is if you lie to or steal from someone. Even if you are not discovered by anyone, inwardly, you will feel fearful. Because of this action, and the fear that arises as a result of this action, you will not be able to live a worry-free, relaxed, and open life.

When babies smile, they do so in a manner that is pure and free because they have no hidden thoughts. When adults smile, on the other hand, because they have many hidden thoughts, their smiles are not as pure or innocent. Ordinary sentient beings are filled with the three poisons and have many vexations. When we see images of the Buddha smiling, they are innocent and pure because the Buddha has no vexations and is not affected by the three poisons. When we see the Buddha or a baby smile, we immediately feel comfortable because they do not have vexations. They reveal in their smiles complete satisfaction and pure joy.

Intrinsically, everyone is like the Buddha, but because our many vexations, outwardly, we cannot manifest ourselves as Buddhas. Everyone should be, like the Buddha, perfect in appearance, but we are not. Venerable recounted a story about one of the first seven-day retreats he attended with Shifu. On the fifth day of the retreat, Shifu said, "The reason all of you are not yet Buddhas is because you are full of vexations. Because you are so full of vexations, you need to repent." He asked us to do prostration repentance. Venerable reflected to himself and couldn't think of any wrongs he had committed, but because everyone was doing repentance prostration, he decided to follow along. Shifu continued, "If you are already perfect, then you would already be Buddhas. The reason you are not perfect and not a Buddha is because there are still a lot of things you have done that are wrong-so you still need to repent." Venerable said that because it was only the first or second retreat he had ever attended, he knew little about repentance and was not able to discover his wrongdoings. He knew there was something he did that was wrong, but was unable to verbalize it or realize it consciously.

The word "repentance" in Chinese is comprised of two characters-- "chan hui." "Chan" means "to discover our misdeeds in body, speech and mind," and "hui" means "to vow not to repeat the misdeed again". The important point is that we discover what we have done wrong. Venerable asked the audience if anyone repents everyday and of what they repent.

In general, when we talk about repentance, it is related to the five precepts or the Bodhisattva precepts. The five precepts are to not kill, not steal, not commit sexual misconduct, not lie, and not take intoxicants. These precepts help guide us mainly so that we may have pure bodies and pure speech, but not for pure consciousness or mind. The ten virtuous precepts protect the conscious or mind.

There are many subtle levels in keeping the precepts. Venerable gave the example of a person who walks in the woods and sees some wild fruit. Would picking and eating the fruit be considered stealing? A person who is strictly upholding the precept of not stealing would not pick the fruit because it does not belong to him or her.

Another example Venerable gave was that of a practitioner who smelled the fragrance of a lotus flower and thought, "Ah, it smells so good." The dharma protector revealed itself and said, "How can you steal the fragrance of the flower?" The practitioner responded, "Why did you scold me? Everyone is doing it". The dharma protector said, "I scolded you because you had vowed to uphold this precept very strictly, that is why I am making sure you do not do that. Other people keep the precept at different levels." Venerable then asked, "Do you think a Buddha smells and hears what he wants to?"

Ordinary sentient beings repent from the point of view of the five precepts, which are a well-defined set of behaviors. The bodhisattva precepts are higher level in that they cover consciousness or intention.

There are two types of repentance-repentance of form and subtle or formless repentance. In the monastery, a repentance liturgy is chanted as part of the morning and evening services --

All bad karma created by sentient beings

Coming from greed, hatred and ignorance

Since time without beginning,

Arising out of body, speech and mind

For all this the sentient beings do repent.

This liturgy covers both form and formless repentance. Repentance of form is repentance for karma arising from body, speech and mind, and formless repentance is karma arising from dualistic thought. Formless repentance is a deeper level of repentance where one may enter into a state beyond dualism, even into the state of nirvana. This is a very high-leveled form of repentance practiced by the Sixth Patriarch.

All misdeeds arise from the mind, so we repent from the mind. If the mind subsides or diminishes, then the misdeed disappears. When the mind and the misdeed diminish together, this is called repentance. When the mind and misdeed are both empty, we call this emptiness. Both mind and bad karma don't have inherent self-nature or characteristics. If a misdeed is permanent and unchanging, then we would not be able to get rid of it because it is always there. If you commit a misdeed, you can repent of it and it will be gone because the nature of the misdeed is empty, ever-changing and impermanent. Emptiness does not mean that there is no phenomenon, that if a person kills another person, that situation does not exist. Emptiness means that the situation will not always remain the same--because there is nothing permanent, phenomena will change due to causes and conditions.

In the example of the practitioner smelling the flower, if there is a subjective "I" smelling the flower, then already dualistic thought exists. The reason we are not like the Buddha is because we have dualistic views and thoughts. Ignorance comes from this dualistic thinking. We need to repent of our dualistic thinking. If we cultivate ourselves through practice, someday we will become like the Buddha.

Venerable gave another example-- if you watch a movie and see someone commit murder, and you have the thought that the murderer should be killed, even if it is just a thought, if you have taken the bodhisattva precepts, you have already broken the precept of no killing. This is because the thought of killing the person is already a dualistic thought-there exist the person who killed and an "I" that is thinking the thought. Then your chance of attaining Buddhahood is gone.

During the day, when you watch the movie, you may see someone doing something bad and you give rise to the thought that he should be killed. But this thought may not be very clear. At night, in your dreams, the thought that this person should be killed may be very vivid. It is actually only a wandering thought, but in your dreams this wandering thought is very vivid and you become entangled by it. If, during the day, you do not have the thought of breaking the precept, you will probably have better dreams. Even though you still have dualistic dreams, at least they are good dualistic dreams.

Because all phenomena are intrinsically empty, ordinary sentient beings are able to attain Buddhahood. Because all things are empty, we are able to commit bad, good and all different kinds of deeds.

For example, if someone killed another person, throughout this process, the mind does not give rise to an idea of an "I," yet there is the act of killing and the other person being killed, then he is not committing any crime. This practitioner has reached the stage called "empty of the three realms." A person who has attained this level would never kill. We use that example to demonstrate the nature of emptiness.

On the other hand, when ordinary sentient beings kill, they have the idea of "I" killed another person very firmly in their minds. Because fear arises in their minds, another person gives rise to a sense of wanting revenge.

When we kill and we have a concrete belief that "I" killed someone, we still have memories. We have imprinted in our minds what had just happened, and each time we think of that event, that image in our memory seems true to us, and that action of killing is still really happening, as well as the existence of the person that we just killed. In reality, it's all just a memory in our minds, but when we think about it, it's just like the real thing, again and again.

The force of dualistic thinking, or the differentiation of thought and thinking, creates ignorance. This ignorance becomes more and more powerful, and becomes cemented in our mind as part of our understanding. Thus, phenomena seem very concrete, and our dualistic views repeat again and again, life after life, and our ignorance becomes more and more powerful.

The force of dualistic thinking, or the differentiation of thought and thinking, creates ignorance. This ignorance becomes more and more powerful, and becomes cemented in our mind as part of our understanding. Thus, phenomena seem very concrete, and our dualistic views repeat again and again, life after life, and our ignorance becomes more and more powerful.

Another example Venerable gave was that of encountering a person you don't like. If you dislike someone, you think, I dislike this person. Each time the thought of this person arises in your mind, you dislike this person. The same thing happens when you like someone. Each time the thought of that person arises in your mind, you like this person. This is how ordinary sentient beings reinforce and repeat ignorance, as well as karmic force.

Venerable advised that we should repent like this: each time a memory arises, we should clearly know that it is not real, that it is arising from our minds, and not react. Each time we practice this, we diminish the power of our ignorance. This, Venerable said, is true repentance. Each time we practice this, we recognize that it is just another memory.

The nature of emptiness does not violate the law of causes and conditions. An enlightened person does not give rise to a sense of "me", "others" and phenomena. To this person, all are empty. Before being enlightened, if this person committed good or bad karma, the karmic force still exists, and the person will still be governed by causes and conditions. The difference between an enlightened being and an ordinary sentient being is that the enlightened being will go though retribution but not have a sense of the self going through it. For example, the enlightened person may feel physical pain, but have no sense of "I" feeling the pain, whereas the ordinary sentient being will have a strong sense of "I" feeling the pain. This is because before being enlightened, they have accumulated eons and eons of karmic force, and when it has ripened, they have to face the karmic force or retributions, but they just go through it, without an "I".

Shifu had said that when we practice meditation and feel leg pain, we should acknowledge that it is just leg pain, but "I" am not feeling the pain. We should just experience the phenomena, but there is no self experiencing it. Ordinary sentient beings, because they have not trained their minds, experience not only the physical pain but the mind-to them, there exists also the psychological pain.

For example, someone who lost $100 million in the stock market crash not only lost $100 million, but experiences psychological distress. When a wife is being beaten by her husband, not only does she experience pain in her body but in her heart. The enlightened person, on the other hand, when encountering the karmic retribution of being hit, will think, that is the phenomena of being hit, and feel no residual feelings of hate, regret, or a sense of unfairness. Ordinary sentient beings may feel anger, want revenge, or do something in response.

Even though we are not enlightened yet, and haven't yet experienced the nature of emptiness, we should practice repentance. Each time we give rise to anger, we should recognize that the anger is resurfacing from our memory, and repent. Each time we do that, we are in accordance with the nature of emptiness.

We can practice true repentance every day, and gradually increase the frequency of repentance. Each moment a thought surfaces, we can realize that it is just a memory, that we are getting upset with our own memory, and immediately get closer to experiencing the nature of true emptiness.