| |

Summer 2003

Summer 2003

Volume 23, Number 3

|

To

the Women's Prayer Breakfast for Peace To

the Women's Prayer Breakfast for Peace

In the year 2002, according to estimates published by the Munich Assurance Company, natural disasters

cost the world as much as US$550 million and more than 11,000 human lives.

These figures include victims of the floods in Eastern and Central Europe,

the earthquake in Afghanistan, and the heat wave in India, and make 2002 the

most severe of the last six years. In addition to natural disasters, threats

of war, terrorist attacks, traffic accidents and the outbreak of deadly

diseases have caused great loss of lives and resources, creating a sense of

threat to the security of the human race.

Therefore, we gather here today, to pray and to implore the people of the

earth to pray

together sincerely: "May there be peace on earth, stability in our

societies, security for all nations, and peace in everyone's mind".

Although prayer is beneficial, if the idea of peace is absent from people's

minds and

their actions are not devoted to peace, then the word "peace" becomes meaningless.

We must bring our minds and actions into accord with our prayers. If our minds

are filled with conflicts and disagreements on religious, cultural, political, economic, social, and racial issues, if our minds are filled with

conflicts and confusions between selfish desires and public welfare, then we

will be at odds with our prayers. The all-loving God and the compassionate

Buddha will always extend their hands to help the human race, but if the thoughts and actions of the human race come from hatred instead of

compassion, selfishness instead of altruism, antagonism instead of

tolerance, discrimination instead of respect, jealousy and suspicion instead

of trust, then we are contradicting our prayers. This contradiction is not

because God is unloving, or the Buddha uncompassionate ; it is because we,

human beings, have mistaken the direction of peace and joy due to our own confusion.

Therefore, let us pray, and let us also devote ourselves wholeheartedly to the cause of

peace. That way, a beautiful and peaceful tomorrow will definitely manifest in our world

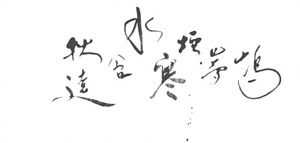

-- Master Sheng Yen, to the Woman's

Prayer Break-

fast for Peace IN Washington D.C., January 9, 2003.

|

Chan Magazine is published quarterly by the Institute of

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Culture, Chan

Meditation Center, 90-56 Corona Avenue, Elmhurst, New York

11373. The Magazine is a non-profit

venture; it accepts no advertising and is supported solely by contributions from members of the Chan Center and the

readership. Donations to support the Magazine and other Chan Center

activities may be sent to the

above address and will be gratefully appreciated. Your donation is tax deductible.

For information about Chan Center activities

please call (718)592-6593.

For Dharma Drum Publications please call

(718)592-0915.

Email the Center at ddmbaus@yahoo.com,

or the Magazine at chanmagazine@yahoo.com,

or visit us online at http://www.chancenter.org/

ęChan Meditation Center

Founder/Teacher: Shifu (Master) Ven. Dr. Sheng Yen

Publisher: Guo Chen Shi

Managing Editor: David Berman

Coordinator: Virginia Tan

Design and Production: David Berman

Photography: David Kabacinski

Contributing Editors: Ernie Heau, Chris Marano, Virginia Tan,

Wei Tan

Correspondants: Jeffrey Kung, Charlotte Mansfield,

Wei Tan, Tan Yee Wong, Robert Weick

Contributors: Ricky Asher, Berle Driscoll, Rebecca

Li, Mike Morical, Bruce Rickenbacker

From the Editor

From the writer Michele Serra, in the pages of the Italian daily La Reppublica , in

translation: "Any head of state who, in the year of our Lord 2003,

continues to hold up God as the sponsor of his political choices, and

particularly of a war , and continues to define his military objective as the

'Camp of Satan' or the 'Empire of Evil', cannot represent in any way the motives

and sentiments of a civilized people. Fanaticism is fanaticism, and 'democratic

fanaticism' is not a variant that mitigates the noun, but one that makes

meaningless the adjective."

It is the 19th of March, 2003, and some time in the next 48 hours we are evidently

going to war. In the midst of geo-political chaos, and in the face of impending

death and destruction, the quality of my practice seems a tiny thing, but

putting the method down when the vexation is really big would seem not to be the

way. So the fact that I am angry concerns me, and as I observe this anger

arising I note, among other things, that it potentiates certainties in me,

certainties that are equal and opposite to the certainties of those that lead us

into war. In my anger, I know that this war is wrong as certainly as George Bush

knows that his God supports it, and that equivalence of certainty is, and should

be I think, alarming.

Fanaticism is indeed fanaticism, and what nourishes and characterizes it is precisely

certainty, which, whether it proceeds directly from the human ego or from some

idea of the divine, shuts tight the gates of perception, blinds the light of

reason, smothers any possibility of compassion.

Certainly it is certainty that drives this drive to war - the fanatics on both sides are

absolutely certain of their righteousness, openly disinterested in the views of

the other, callous to the point of acknowledging that the inevitable loss of

innocent lives is an acceptable price (for others to pay). Certainly it is certainty that drives this drive to war - the fanatics on both sides are

absolutely certain of their righteousness, openly disinterested in the views of

the other, callous to the point of acknowledging that the inevitable loss of

innocent lives is an acceptable price (for others to pay).

So what am I to make of my own certainties?

We practice in a world in which the spectre of Osama bin Laden, Koran in

one hand and rifle in the other, has now been joined by the equally frightening

image of George Bush wrapped in the flag and brandishing the cross. As we work

for peace, let us not make the mistake of certainty of cloaking ourselves in the

indubitable Dharma, and wielding some poor imitation of the sword of wisdom.

The Editor

The Four Proper Exertions: Part Two

Dharma Talk by Master Sheng

Yen

This is the second of four talks on the Four

Proper Exertions, given by Chan Master Sheng Yen between October 31 and November 21, 1999, at the Chan Meditation Center, NY.

Rebecca Li translated, and transcribed the talks from tape.

The final text was edited by Ernest Heau, with assistance from Rebecca

Li.

In our first talk on the Four Proper Exertions, we

discussed their importance in developing the diligence to practice

contemplation, cultivate samadhi, and give rise to wisdom. Today, we will talk

about the role of meditation in practicing the Four Exertions. Let's first

recall what the Four Proper Exertions are. They are: First, to prevent

unwholesome states that have not arisen from arising; second, to stop

unwholesome states that have already arisen; third, to give rise to wholesome

states that have not yet arisen; and fourth, to maintain and increase wholesome

states that have already arisen. Remember that by states we mean actions as well as speech and thoughts. In our first talk on the Four Proper Exertions, we

discussed their importance in developing the diligence to practice

contemplation, cultivate samadhi, and give rise to wisdom. Today, we will talk

about the role of meditation in practicing the Four Exertions. Let's first

recall what the Four Proper Exertions are. They are: First, to prevent

unwholesome states that have not arisen from arising; second, to stop

unwholesome states that have already arisen; third, to give rise to wholesome

states that have not yet arisen; and fourth, to maintain and increase wholesome

states that have already arisen. Remember that by states we mean actions as well as speech and thoughts.

How do we distinguish between wholesome and

unwholesome states? We take the point of view of wholesomeness as the ten

virtues, and of unwholesomeness as their opposites, the ten non-virtues. We can

also look at wholesomeness and unwholesomeness from the points of view of daily

life, and of meditation. One simple idea is that if you do wholesome things you

won't go to jail, but if you do unwholesome things you can end up in jail. Based

on this simple distinction, it is not always clear what is wholesome and what is

unwholesome. We know that some people do good things and end up in jail, and

some people do evil things and remain free. Someone might steal $1,000 and go to

prison, and another may steal an election and become the president. Someone

commits murder and is executed, while another massacres ten thousand and is a

hero. So how useful is to say that unwholesome people go to jail, and wholesome

people do not?

Because it is not always clear what is wholesome

and what is unwholesome, Buddhism prescribes the ten virtues and their

opposites, the ten non-virtues. We described these in the previous lecture. The

ten virtues give us a clear idea of what wholesome and unwholesome really mean,

and are in three groups: virtues that pertain to actions, virtues that pertain

to speech, and virtues that pertain to thoughts. Of these, Buddhism gives

greatest emphasis to virtues of the mind, because the impulses to act or speak

come from the mind. You can usually tell whether someone's actions and speech

are wholesome, but it is not as easy to tell if their thoughts are. In daily life

we can usually recognize unwholesome states, but it's another matter when we

meditate.

Unwholesome States in Meditation

Without proper training and practice, it is hard to recognize the unwholesome states that may come up when we meditate. They are restlessness, drowsiness, no confidence, laziness, no self-control, scattered mind, erroneous views. Just about every meditator experiences them, making it very difficult to attain samadhi. For the first few days on retreat, you may experience these problems, but with diligence your mind will gradually become more stable and relaxed; you will become

less restless and less prone to drowsiness. When you are no longer restless and drowsy, your interest and enthusiasm will give you the confidence to overcome laziness. You will then find meditating very rewarding.

There is a difference between laziness and lack of self-control. When you are lazy you are passively idling and scattered, but with no self-control you are actively engaging in incorrect views, and even

become liable to to lose control over body and mind. But if you make an effort to

become more stable and more relaxed, you will be able to overcome scattering, control your body and mind, and give rise to correct views,

The right approach is simply to know that the point of practice is to

stabilize body and mind, and to diminish vexations, By becoming stable you will more clearly perceive the subtle vexations in your mind. Recognizing them, you can also stop and avoid unwholesome

states. When you do that you will be able to arouse and maintain the more wholesome states. At that point you are actually practicing

the Four Proper Exertions.

Are You Wholesome?

Though most people would assert that they are good, they are not always clear about what is

wholesome and what is unwholesome. Once a Chinese man told me that he had no religious affiliation. He said,

"Religions teach people to become good, to become wholesome. I know

that." I asked him why he has no religion then. He said, "I do not need religion; I never do bad things; I never have bad thoughts. Only

people who have bad thoughts and do bad things need religion." I asked him, "So you are

really a good person, you really have a good heart?" He said, "Of

course I have a good heart." When I questioned him further, he said, "How dare you question me? What evidence do you have that I am not a

good person, that I have unwholesome thoughts?" I told him, "Well, right now, you are angry. Isn't that unwholesome?" Despite being a

good person, this man could not recognize his own unwholesome thoughts.

Some people thing anger is not such a bad thing, especially when they can blame others for making them angry. They will say, "You made me angry."

They live in suffering and vexation without even knowing it. Some people become angry when they don't get what they want, blaming others, or saying

that life is unfair. But if they do get what they want, they want more. Some are envious if others are better off, but if they find themselves better off

than others, they become proud. Are these wholesome states of mind? You will probably think, "That's just normal!" [Laughter]

From the Buddhist perspective this is vexation and suffering. The purpose of Buddhadharma is to turn suffering into

true happiness, vexation into wisdom, anger into compassion, and greed into a heart of giving. We use

wholesome states to correct what is unwholesome and to cultivate a

genuinely pure and stable mind.

Without meditation it is difficult to see clearly one's own wholesome and unwholesome states, and to know when the mind is pure or impure.

But with meditation practice, your mind becomes stable, clear and able to see its own subtleties. You will recognize and correct unwholesome states

as they arise. for these reasons meditation is basic to practicing the Four Proper Exertions. The

Mahaprajnaparamita Sastra says that practicing the Four Foundations of Mindfulness will eventually give rise to wisdom.

The Five Obstructions

Laxity in practice will give rise to the five obstructions of desire, anger, sloth, restlessness, and doubt, which we described in the previous

talk. When this happens, you won't be able to gain the Five Mental Faculties of faith, diligence, mindfulness, samadhi, and wisdom, which are also part of the Thirty-Seven Aids to Enlightenment. The five obstructions

are in fact unwholesome states that hinder the arising of the Five Mental Faculties.

In daily life, people desire money, fame, food, love, and living comforts. What do we desire when we

meditate? Surely, they should not be the same things. (Answers from the audience:

"Enlightenment, bliss, good feeling.")

Is this what we are seeking the whole time we are meditating? "When am I going to get

enlightened?" Or, "I want supernatural powers." Or, "I want to be at one with the universe." These are desires for experiences, or for just feeling very comfortable and blissful while

sitting for hours. These attitudes will not get you samadhi, much less wisdom , because they are still desires, Not getting what you want to experience

can lead to anger, or disgust.

The mind will become restless, the body will get hot and bothered, and the cushion will feel like a volcano. Instead of getting up from the

cushion people like this will keeping struggling, looking for something they can't get, or had and lost, and creating more and more vexations for

themselves.

After struggling like this for a period of time, you will have lost a lot of energy, and will be tired. This obstruction is sloth, or torpor,

characterized by severe drowsiness. So after sleeping on the cushion for a while, like drifting in a rowboat, you recover from tiredness and begin

meditating again. But then desire and anger come up again, the mind becomes restless, and the internal struggle begins all over. This is the

fourth obstruction, restlessness, or being scattered.

So when one's mind is restless, it leads to the fifth obstruction, doubt. Doubt can be lack of confidence in your teacher, or doubt in the

meditation method that you were taught. Another kind of doubt is in believing that your physical or health problems make your body not suitable for meditation. With doubts like these and others, eventually you will decide to quit, and want to leave

[the retreat] thinking, "Well, the others can meditate, but it's not for me."

So these five obstructions block the virtuous wholesome faculties, and prevent us from eliminating our vexations, and from opening the

road to wisdom and compassion. Now, to encounter the five obstructions is normal in practice, but if we diligently rely on the Four

Foundations of Mindfulness, we can prevent obstructions from becoming serious. When obstructions arise, just return to the Four Foundations of Mindfulness.

Better yet, with continuous practice of the Four Foundations, obstructions will not have a chance to come up in the first place. So these are the ways

to practice the first two exertions, to stop unwholesome states that have arisen, and to prevent unwholesome states from arising.

So when obstructions arise, just return to your practice method; rely on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness. Diligent, ceaseless use of the

meditation methods and practicing the Four Foundations will help us stop unwholesome states, and not allow the rising of new ones.

The Five Mental Faculties

We said earlier that with the five obstructions prevent the Five [Wholesome] Faculties from arising. On the other hand, practicing the

Four Foundations of Mindfulness will give rise to the five faculties, which we said consist of faith, diligence, mindfulness, samadhi, and

wisdom.

Let's begin with faith. There are several reasons for having faith in something. First is to have blind faith in something because others do,

or tells you to. I once asked someone why he was a Buddhist. He said, "My wife wouldn't marry me unless I became a Buddhist, so I became a

Buddhist." This is blind faith, but it is not necessarily bad. This man eventually became a good practitioner.

You can also have faith in something you understand. When you learn the principles and the doctrines of a belief and find them suitable, your belief

is based on understanding, not just blind faith. Very often Westerners, especially intellectuals, turn to Buddhism because they understand and feel

compatible with the ideas.

Another basis for faith is first-hand experience. When you put Buddhism into practice and find that it improves your life, stabilizes your

mind, and helps you to help others, this builds confidence and faith in Buddhism. This is the kind of faith that is the first wholesome faculty.

We have said that the practice of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness is the path to samadhi. But samadhi by itself does not give

rise to wisdom. The Five Methods of Stilling the Mind can stabilize the mind, but the Four Foundations emphasize going beyond stilling the mind, and

diligently practicing contemplation to arouse the wholesome faculties. Through diligence we can eliminate vexation and attain wisdom; without

it, arousing the Five Mental Faculties would be very hard. When faith arises, diligence will naturally arise with it. This is because seeing the

useful results of practice, one will become more confident, and one will want to work very hard to keep getting good results. This willingness

to work hard is diligence.

The third wholesome mental faculty is mindfulness, which means always keeping the practice foremost in your mind. More than thirty of you

took the Three Refuges with me to day, but will it be two years before I see you again? If that happens, you have not given rise to mindfulness,

and maybe you will have forgotten the practice. So to be mindful, remind yourself that the Dharma - the practice - is very important and very

will become diligent in your practice. The third wholesome mental faculty is mindfulness, which means always keeping the practice foremost in your mind. More than thirty of you

took the Three Refuges with me to day, but will it be two years before I see you again? If that happens, you have not given rise to mindfulness,

and maybe you will have forgotten the practice. So to be mindful, remind yourself that the Dharma - the practice - is very important and very

will become diligent in your practice.

And being diligent, you will be able to enter samadhi, and eventually give rise to wisdom.

I had a student who participated in a seven-day retreat with me, and then didn't show up for another five years. Then another five years later

he showed up again, so I asked him, "How come I haven't see you for the last five years?" And he said, "Shifu, at least I came back. Some

people never do."

Snakes and Ladders

a poem by Mike Morical

|

I

Rescue Ladder

floats in a melted lake,

bobbing in place.

What holds it there?

Why won't it drift this way?

II

Staircase, not house:

climb and jump back

in the desert, burning.

A cactus blossoms. Refuge

rain from barren sky.

|

|

Solitary Practice: "To the Noble Monk

Cheng"

By

Chan Master Zhongfeng Mingben

Translation by Guo Jue

Zhongfeng Mingben (1262 -1323) was an eminent Chan master of the Linji lineage in the Yuan Dynasty. He was a student of Chan Master Gaofeng Yuanmiao (1239-1295) who entered into the mountains when the Mongols took over the country. Gaofeng was the protagonist of the famous gongan, "Do you have mastery of yourself when you are in a dreamless sleep?" Zhongfeng attended to his teacher for several decades in the mountains, living in arduous material poverty and hardship. He became one of the very few to have received transmission from Gaofeng. Later on, he traveled a great deal around the country. There were times when he would live in a boat for months. Wherever he stayed, he called it the illusory abode and called himself the "dweller of the illusory abode".

Guo Jue is a student of Master Sheng Yen who lives in Maryland. He is an enthusiastic

reader of the classics of Chinese Buddhism, and the translator of "A Guide to Sitting" by Changlu Zongze, which appeared in the Summer 2002 issue of Chan Magazine.

Practitioners of old often went to live in solitude when they had not yet

awakened from their own affairs [of birth and death]. Living in a thatched shack to work on themselves, they did not get involved in

the world initially. They practiced in all daily activities, be it: planting rice,

working in the field, wearing straw cloth, surviving with food gathered

in the woods, drinking from the streams, cooking with a broken utensil,

making a bed out of withered tree trunks, or fashioning a stove

using pieces of wood. Some of them lived solitarily for twenty or thirty

years in the remote mountains, making no contact whatsoever with the

outside world. [When interacting with those who came to learn from them,]

some showed the woven bamboo belt they wore, some raised their fists,

some pointed with a finger, some threw around huatous such as "the stream

is deep and the handle of the spoon is long." Manifesting all sorts of actions, their styles and dispositions were lofty and awesome

, sending shocks through the eyes and ears [of those who came into contact with

them.] The light of their splendors shone, illuminating thousands of years of

time. All these actions occurred without an iota of contrived intention or

expectation.

Later on, the way of living became more decadent; human minds became weaker.

Practicing in solitude became a scheme to live in idleness and laxity. People

did so to avoid the restrictions and rules of a large monastery. They did it

so that they could sleep and go freely whenever and wherever they wanted. By

and by, they all became outer path followers who searched only for physical

freedom. Not only is this practice useless in aiding one along the Path, it

causes one to drift farther and farther down the stream [of desire] to the

point of no return. These people would unconsciously start to engage

in all sorts of inverted and discriminating practices of mundane affairs,

in addition to a life of idleness and laxity. Such people would become engulfed by the mundane and

worldly.

[One should understand that] when the Buddha and the ancestral masters

established a place of practice, whether it was a place large enough

to accommodate ten thousand people or just big enough for one person

,the essence and substance is having [the mind on] the Path. If one were clear with the Path, even if one lives among ten thousand people,

one would not feel the excess of the multitude; if one were to live in

solitude, one would not feel the want of companionship. Because of the

absence of such a feeling [of excess or want], one might as well call living

among the multitude as living in solitude, and call living in solitude as

living among the multitude. If one can assume the attitude of living in

solitude when one is among the multitude, one would not be bothered by

the presence and interactions of people around oneself; if one can assume the attitude of living among the multitude when living solitarily,

one would not be deluded by the sorry physical condition of leaking roof and unlighted shack.

[One should understand that] when the Buddha and the ancestral masters

established a place of practice, whether it was a place large enough

to accommodate ten thousand people or just big enough for one person

,the essence and substance is having [the mind on] the Path. If one were clear with the Path, even if one lives among ten thousand people,

one would not feel the excess of the multitude; if one were to live in

solitude, one would not feel the want of companionship. Because of the

absence of such a feeling [of excess or want], one might as well call living

among the multitude as living in solitude, and call living in solitude as

living among the multitude. If one can assume the attitude of living in

solitude when one is among the multitude, one would not be bothered by

the presence and interactions of people around oneself; if one can assume the attitude of living among the multitude when living solitarily,

one would not be deluded by the sorry physical condition of leaking roof and unlighted shack.

Living solitarily in this manner, thought after thought, one would be

in touch with all humans and devas; in all places, one would be meeting

with the saints and sages of old. Even events that happened thousands

of years ago could be felt as if they are happening in front of one's

very eyes. Thus, it would be alright if one is poor, and it would be equally

alright if one is not poor; it would be alright if one has visitors, and it

would be equally alright if one has no visitors; it would be alright if one

engages in all sort of functions and affairs, and it would be equally

alright if one engages in nothing at all throughout the day. Whatever one

encounters, be it affliction or joy, unfavorable or favorable situations,

to the point that if myriad conditions were to manifest in front of one's eyes simultaneously, all moments are the right moments to raise

one's fists and fingers. There would be no shack dweller to be found, and

there would be no non-shack dweller to be found; there would be no happenings

to be seen inside the shack, and there would be no happenings to be seen

outside the shack. [At this point,] true reality would permeate everything;

all [deluded] thinking would have completely subsided; the feeling of being

right or wrong would have been ended, and the dualistic understanding of subject

and object would have been gone. Then one would know that when the old

lady burned down the shack, and when the old adept scribbled the word "mind" on the door, they were all painting a golden hue on a piece

of gold, adding light to the brightness of the sun. This is the proper

way of practicing solitarily in a shack.

If this is not the case, it is unavoidable that one would feel the outward

presence of the shack, engendering feelings of opposition and expectation,

parting and coming together; bringing about the constantly - changing

emotional vicissitude of grabbing, releasing, liking and aversion. Alas!

This condition is precisely why we said that the affair of birth and death is grave and impermanence strikes fast and unexpected.

One should understand that if one goes into solitary practice without

the utmost essential motivation of resolving the affair of birth and

death, when the end of life comes, [the realm of] birth and death would be the shack in which one dwells,

amidst broad daylight. One would be engulfed by it.

You should always contemplate in this manner. Do not let yourself drown in delusion during daily activities and lose focusing the mind

on the Path.

A Mind-Stopping Experience

practitioner's report by Wing Shing Chan

This occurred during a trip to hear a lecture by Shifu (Master Sheng Yen)

about ten years ago.

I had moved to New York, near the Chan Center, in order to learn Buddhist practice with Shifu. I devoted most of my time to practice while at

the same time writing my dissertation for an academic degree. My house was only a five-minute drive to the Center, which made it easy for

me to participate in almost all of the Center's open activities such as retreats, lectures, classes, and often the early morning meditation session

and service with the resident monks and nun. When Shifu lectured outside the Center, even in neighboring states, I would follow without

exception. These opportunities to learn directly with Shifu motivated me and fine-tuned my methods and concepts of practice. I was aware that

my practice was improving at a much faster pace than when I had been practicing on my own.

The lecture was held in November 1993 at Temple University in Philadelphia, and Shifu was going to speak on a Chan topic in a small classroom. I had been

offered a ride and arrived early together with Shifu. I was therefore able to find a seat in the front, quite close to the table where Shifu was sitting.

The seats mostly filled up, and after a brief introduction Shifu began to speak.

Shifu had been given a wireless microphone standing on the table next to a portable amplifier with loudspeaker. Several minutes after Shifu began to

lecture, the loudspeaker began to emit a loud humming sound that interrupted Shifu's speech. Shifu tried knocking lightly on the microphone but the humming

sound went on. No side the Center, even in neighboring one around was able to offer help. The lecture came to a halt.

Electronics had been a hobby of mine before, so I was quick to realize that the problem was a

positive feedback due to the microphone being too close to the loudspeaker. With no further

consideration or hesitation, I stood up and went forward to adjust the microphone. Just at the

moment when I was about to grasp it, Shifu suddenly withdrew it swiftly; my hand grasped only the empty space. I was shocked - Shifu's action was so

unexpected. The microphone being adjusted, the humming sound disappeared and things went back to normal. There was no need for me to

do anything any more so I returned to my seat.

As soon as I sat down to listen to Shifu's speech again, I realized that something was different in me: not a thought was able to arise in my

mind. (Because I had been practicing meditation for some time I was aware of the movement of my discursive thoughts during my daily

life.) In other words, my mind of discursive thoughts had stopped. I could still listen to and understand Shifu's lecture. I could still perceive

the other people and the surrounding environment. There were simply no

discursive thoughts, The world was much quieter and clearer. My thoughts, speech and body movement became much more spontaneous. I had experienced the

stopping of discursive thoughts before during retreat or meditation practice, but this was the first time it had occurred without meditating,

This was being helped by Shifu, I think. This state of no discursive thoughts went on as I returned to the Chan Center after the lecture, and

was with me for a couple of days.

The experience reminded me of what Teshan had experienced under Master Lungtan (Example 28 of Wumenkuan):

Once Teshan was asking Lungtan for instruction late into the night. Lungtan said,"It is the middle of the

night. Will you not retire?" Teshan took his leave, raised the door hanging, and went out. As he saw the darkness

outside, he turned around and said "Dark outside."

At this Lungtan lit a paper torch and hand it to him. Teshan was about to take it when Lungtan blew it out.

All a sudden Teshan had a moment of insight. He prostrated.

Lungtan said, "What truth did You see?"

Teshan said, "From now on this one here [I] will not harbor any doubts about the words of the old master [famous everywhere] under

heaven."

I do not claim that I had an experience equal to that of Teshan. The above kungan (koan) is only meant to illustrate the similarity between

masters in their ways of working with students, Indeed, in hindsight, I do not think that my experience of no-thought-arising was thorough

or complete.

It appeared as if a certain internal 'force' due to dhyana practice had blocked the 'outlet' and suppressed the thoughts from arising. It was not

until years later, after much further practice, that the keeping of a no-thought-arising state had become natural, smooth and effortless.

The Past

News from the Chan Meditation Center and the

DDMBA Worldwide

Women's Prayer Breakfast for Peace

On January 9, 2003, about 250 attendees gathered in Washington, D.C. for the Women's Prayer Breakfast for Peace, organized by the

Global Peace Initiative of Women Religious and Spiritual Leaders.

The Prayer Breakfast began at 7:30 in the morning. Activities included prayers from each religion and presentations on special topics with

the main focus on "Peace and Prayer."

Participants expressed and exchanged thoughts and ideas. Despite the cold drizzling weather in Washington D.C., the attendees, among which were leaders in religion, government, and business, gathered

in the ballroom at the Willard Intercontinental Hotel. Also present were five male participants invited to participate at the Prayer Breakfast. Religious representatives present included those of Buddhism (from the Chinese, Tibetan, and Theravadan traditions), Christianity,

Judaism, Catholicism, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Sufism, and the Inca tradition. In addition to participants from United States and neighboring

Canada, some came from as far as Thailand, India, Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

Venerable Guo Yuan Fa Shi, attending the Breakfast on behalf of Chan Master

Sheng Yen of the Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association, read a speech by the Master (full text on page 1 of this magazine) and

recited the Heart Sutra in his prayer for peace. The Prayer Breakfast adjourned at noon.

American Buddhist Confederation Celebrates

Chinese New Year

Over a billion Chinese around the world ushered in the Year of the Ram on February 1, 2003. The American Buddhist Confederation celebrated the occasion on February 8 at the Chan Meditation Center/ Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association in Queens. Guo Yuan FaShi, ABC's current president, played host in the absence of Master Sheng Yen to 46 monastics and 15 lay Buddhists from 20 different

member organizations from the metropolitan New York area. Guo Yuan Fa Shi

expressed regret that Master Sheng Yen was in Taiwan and unable to meet them in person, but the Master sent his blessings and good wishes to

all the guests. Each year ABC members take turns hosting the celebration; lt had been more than 10 years since the event last took place at CMC. Over a billion Chinese around the world ushered in the Year of the Ram on February 1, 2003. The American Buddhist Confederation celebrated the occasion on February 8 at the Chan Meditation Center/ Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association in Queens. Guo Yuan FaShi, ABC's current president, played host in the absence of Master Sheng Yen to 46 monastics and 15 lay Buddhists from 20 different

member organizations from the metropolitan New York area. Guo Yuan Fa Shi

expressed regret that Master Sheng Yen was in Taiwan and unable to meet them in person, but the Master sent his blessings and good wishes to

all the guests. Each year ABC members take turns hosting the celebration; lt had been more than 10 years since the event last took place at CMC.

The guests nibbled on snacks while viewing a video of Shifu's new year address

in which he

described the various journeys he had undertaken in 2002, including highlights of the 500-person Chan pilgrimage to China, a separate trip to the mainland to return a stolen Yuan

dynasty Buddha's head, and his meetings at the World Council of Religious Leaders. The group then gathered in the main hall to make special offerings to the Buddhas, and to hear a talk by the elder Ven. Master Jen Chun, who spoke about world instability and admonished sangha members and all Buddhists to serve as role models by exemplary behavior of body, speech and mind.

The Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi, abbot of the Bodhi Monastery in New Jersey, was the guest of honor. He is an American Bhiksu who recently returned to the U.S. after spending over 30 years abroad,

including 10 years in Sri Lanka. He talked about how consumerism has damaged our environment and the dangers of the impending war, and he stressed the need for Buddhist teachings in our

society.

The guests, filling six round tables, were treated to a ten-course banquet, catered by Zen Palate, the famed vegetarian restaurant in New

York City. They were entertained while the food was being served, by the DDMBA choir and various sangha members. Monastics received traditional red envelopes" as gestures of gratitude.

Many thanks to the CMC/DDMBA volunteers, whose dedicated service

contributed greatly to the success of the event.

DDRC Celebrates

Chinese New Year

On January 25, 2003, a warm winter Saturday, the Dharma Drum Retreat

Center Celebrated the Chinese New Year with more than 60 guests, many

of whom were neighbors and town residents. Ms. Maureen Radle, a

regular in the Wednesday night meditation group, kicked off the

event by explaining the significance and meaning of the New Year, and

how Buddhists celebrate the occasion. She also introduced the

various activities and programs held at DDRC.

Guo Yuan Fa Shi expressed regrets to the guests that Master Sheng Yen

was unable to receive them in person but extended his good wishes

and New Year blessings. He related the two important journeys that

Master Sheng Yen had made to China last year complete with photos

of the events. Town Supervisor John Volk talked about how DDRC had become a familiar organization in the town of Shawangunk, and how DDRC's liaison Monita Choi had frequented the office.

The guests feasted on a sumptuous vegetarian lunch, prepared by

volunteers. Entertainment included a children's acrobatic show, DDMBA/ CMC's choir, a "health" dance, David Ngo's taijiquan exhibition; and a flute performance. Guests participated in taiji movements to the sounds of the flute, and in a competitive game of solving Dharma puzzles using Master Sheng Yen's teachings.

This annual event is an occasion to promote mutual understanding between the residents and staff of the Retreat Center and our neighbors in Shawangunk.

C.W. Post College Campus Lecture

On February 22, 2003, a rainy, blustery winter Saturday, Guo Yuan Fa Shi traveled to Long Island's C.W. Post College campus to give a two-hour lecture on "How to Live

a More Meaningful Life" to the 36 students in Professor James Woodcock's

psychology class.

The students were unfamiliar with Buddhism and its teachings. Guo

Yuan Fa Shi began the lecture with a story related by Master Sheng

Yen: Walking with his father one day when he was a child, watching ducks

swimming on a pond, his father had told him that each duck, small and

big, had to find his own way. Guo Yuan Fa Shi told the class that like

the ducks, we too must seek our own path in life. He then introduced

Chan, its methods and the different levels one can achieve, and fielded

many questions.

Professor Woodcock, a Buddhist and disciple of Master Sheng Yen, arranged

this lecture to broaden his students' knowledge and experience.

Long Island Multi-Faith Forum

(LIMFF) is an event that tries to shed light on the diversity of people and

their religious faiths. The LIMFF is headed by Arvind Vora, and organized by Barbara Dorfman and Werner Reich. They have provided a safe place and time to share different views and attitudes towards life, and

especially spiritual values and experiences. Designed particularly for

high-school students, the LIMFF gives the students a chance to interact

with people of various religious faiths. At this year's forum, held at

Hauppauge High School on Long Island, freshman students spent a

few class periods exploring and learning about people of diverse

background and beliefs, including Sikhs, Jews, Brahmins, Hindus, Buddhists,

Unitarian/Universalists, Jains, Bai'Alias, Muslims, and Native

Americans.

Informal presentations were in the gym, which was filled with displays of various physical objects of religious ritual and symbolism:

statues, clothing, jewelry, symbols, places of worship, languages, and sacred objects. There was the music and other sounds of faith, and most importantly at each table, people of various faiths talked about their experiences, their beliefs, and their customs.

Sitting in at the Buddhist presentation table, volunteers from nearby

Stony Brook University had come to introduce the high school freshmen

to their faith and practice. Frank Yao, Fei Ji, and Laura Huang, members of

the Stony Brook Buddhism Study and Practice Group, had been invited to attend by Hai-Dee Lee, an active member of the Chan Meditation

Center. They presented elementary sitting meditation and basic Buddhist ideas to the curious students.

In addition to the informal displays about each religion, there were panel

discussions held throughout the day. Representatives from each faith gave 15-minute presentations that covered the origin, history, beliefs, and practices of their religions. Representing Buddhism was Reverend

Madeline Ko-I Bastis of the Peaceful Dwelling Project, and Robert Festa and Hai-Dee Lee of the Stony Brook University Buddhism Study and Practice Group.

The day was beneficial for the presenters as well for the students. During

the breaks the volunteers from each faith had the opportunity to

meet each other and discuss their beliefs, or just relax and chat. I had

some pleasant discussions with others, a Brahmin in particular, which

reminded me that the Brahmins had lived alongside the Buddha 2500

years ago, and that Buddhist ideas may have been shaped by such dialogues.

The Long Island Multi-Faith Forum is presented in the hope that by meeting with, talking to, and practicing some of what different religions have to offer, the seed of openness and acceptance of others will be planted among the students who attend. For announcements about next year's forum please check the Stony Brook Buddhism Study and Practice Group website at:

www.sinc.sunysb.edu/Clubs/buddhism.

Buddhist and Catholic

Interchange

Guo Yuan Fa Shi was invited to an interchange between Catholics and

Buddhists on January 31, 2003, sponsored by the Commission on

Ecumenical and Inter-religious Affairs, and held at the Inisfada/St. Ignatius Retreat House on Long Island, New York. A group of about a dozen arrived in the afternoon, had a vegetarian lunch, meditated for half an hour, then started an informal interchange. The participants were no strangers to each other, having met on several prior

occasions.

Three Buddhist organizations were represented: There were disciples of Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn, a representative from the Chuang Yan

Monastery in Carmel New York, and Guo Yuan Fa Shi of the DDMBA/CCM/DDRC. Each explained his own organization's goals and

programs. Most of the Catholic participants have had Zen

experience; some are even Zen teachers, but many were also

interested in knowing more about Buddhist practices. The group

compared various concepts of the two religions, and there was a lively

discussion of how to deal with people and situations in daily life in

accordance with God's and Buddha's teachings.

Beginner's Dharma Class

Members of the Dharma Lecturer Training Program presented the Beginners' Dharma Class on three Friday evenings in March. The course

uses Setting in Motion the Dharma Wheel, Shifu's pamphlet on The Four

Noble Truths, to introduce the central ideas of Buddhism. Approximately

twenty students attended the course, which will be offered again

this fall. The dates of the next offering will be announced as soon as

they are determined. Persons interested in taking the course should contact the Center.

Back

|

|