Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 98, July 1993

Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 98, July 1993

Ch'an: Thus Come, Thus

Gone

Lecture given by Master Sheng-yen on the Surangama Sutra on November 4, 1990

Ch'an is "thus come, thus gone." Everything is Ch'an; this is "thus come." Nothing is Ch'an; this is "thus gone." Today I want to investigate these words. I think they will give you new insights into using Ch'an

in your daily life.

The Ch'an sect does not believe in establishing set words, descriptions or theories. In fact, Ch'an cannot be expressed in words or phrases. Anything said about Ch'an cannot be true Ch'an. Nonetheless, Ch'an literature in both China and Japan far exceeds that of other Buddhist traditions. It includes discourses of the masters, discussions with disciples, as well as other writings.

D. T. Suzuki first introduced Zen (Chinese: Ch'an) to the West. In English alone he wrote over twenty books about Zen. Some of my students have compiled my lectures and made them into books. We have published six in English. Even though Ch'an cannot be expressed in words, books keep appearing.

Ch'an can be described from three perspectives: a way of life, a way of dealing with situations, and an orientation toward the external world.

Even an intellectual understanding of Ch'an practice is of some use. But when you go a step further and base your life upon the practice, the characteristics of Ch'an manifest in whatever you do. You find peace, stability, and joy.

Ch'an is open and broad and all-encompassing. There is no rejection of what does not fit your way of thinking. Once you have developed an understanding of Ch'an or perhaps have had a true experience of Ch'an, wisdom manifests in whatever you do. You become aware of a new attitude in yourself that is broad and open and non-discriminating. Others will see it, too.

You reach a point where your understanding of Ch'an accords with what you feel, your sense of justice, and the mores of society. Such harmony is not easy to attain. Your feelings may collide with your sense of justice and propriety. And your sense of justice may clash with what is prescribed by law. But Ch'an is an all-encompassing attitude.

"Thus come" means the attainment of Buddhahood. This is where the practice of Ch'an leads. An experience of "thus come" is an indication that Buddhahood is not far off.

"Thus come" is the generally accepted translation of the Sanskrit, "Tathagata." However, "thus come" is not exactly correct. Tathagata actually means "as if has come but has not really come."

Further, Tathagata has the meaning of "originally it is like this." Originally like what? The original state of every sentient being, namely "as if come."

Are we truly in this world? If we are really here, how does it happen that we leave? Are we really in the Ch'an Center? Is this all there is? In regard to any place, we can say, "it's only as if we have come."

When he attained Buddhahood, the Buddha saw that it was as if he had come -- Tathagata. And when he looks at us, he sees that we, too, are "thus come" and "originally like this.''

We lack this understanding. We are filled with vexation. We attach to what we see, and we are endlessly conflicted. We are at war with one another and within ourselves. This is really quite strange.

We lack the confidence to say that we, also, are "thus come." Aware of the endless vexation in our lives, we find it impossible to affirm that we are the same as Buddha -- that we are ''thus come." Only those who have attained Buddhahood recognize that ''thus come'' is common to all.

How are we to understand what is meant by the terrm, "thus"? There are four perspectives, which correspond to different levels of understanding.

The first perspective is that of ordinary sentient beings. They see the Buddha as the savior of the world, the one who solved the problems of birth, aging, sickness, and death.

Yet, someone once asked me why it was that Sakyamuni himself succumbed to all of these vexations: "How can he help us when he couldn't solve his own problems? It seems that the Buddha has brought us nothing."

Is there really inconsistency here?

The Buddha helped sentient beings overcome suffering through his teachings and through the methods of practice he prescribed. We can practice so that, like the Buddha, we can abandon our self-centered attachment and find our own innate wisdom. No longer will we look upon the process of birth, aging, sickness and death as suffering. We will see that they are the consequences of our own actions.

One who has attained liberation still experiences aging, sickness, and death, but his attitude is that he is merely repaying a debt. Once the debts are paid, nothing is owed. There is no resentment or resistance. This is liberation from suffering. After liberation, one does age, sicken, and die, but there is no fear of the process.

The second perspective is that of the sages and saints of Buddhism, those who have practiced Buddhadharma and have achieved significant attainment, such as bodhisattvas and arhats. From their point of view, the Buddha personifies great compassion, wisdom, and liberation. Ordinary sentient beings believe that the Buddha is a great being, but they have no real comprehension of his greatness. Only the saints and sages truly understand how great the Buddha is. They see that not only is he a great being compared to ordinary sentient beings, but that he is a great being compared to all other saints and sages.

Compassion is a measure of greatness. Ordinary sentient beings usually care for their own family, but they often lack compassion for those outside the family.

Great political leaders may love their country as much as their families. They feel about the citizens of their country and the sanctity of the state as much as they do about their own parents and children. They do not necessarily put their family first. Such compassion is much greater than that of ordinary people.

Great philosophers and religious leaders not only love their own country, but they extend their love to all of humanity. They not only love those who love them, but they love even their enemies. Their love does not discriminate.

Buddhists understand the importance of compassion, not only for humankind, but for all living beings, human and non-human alike. Not all Buddhists attain this level, but it is a fundamental tenet.

A householder practitioner I know always speaks of compassion. One day I saw him with a banana and said, ''I'm hungry, let me have the banana.''

"I have only one banana."

''But, you must have compassion for me, too."

Finally, he retorted, "Let me first have compassion for myself. A Bodhisattva must look after all sentient beings. I'm a sentient being. Let me be compassionate to myself."

This is the compassion of an ordinary sentient being. It is an intellectual concept, not Buddhism.

Compassion is not just a concept to Buddhist saints and sages; it is what they practice. Of course, the compassion of ordinary bodhisattvas and accomplished arhats reveals the level of their attainment.

A story that illustrates this concerns an arhat who professed a willingness to do anything for other sentient beings. A Dharma-protecting deity who wanted to test him appeared, disguised as an ordinary person with a severe ailment. "My physician said that only the eye of an arhat will cure me." The arhat knew this would be painful, but he decided to sacrifice his eye for the other's benefit. He tore out his left eye and gave it to the deity.

But the deity exclaimed, "Wait a minute, you acted too fast. My doctor assured me that only your right eye will do." The arhat plucked Out his second eye, but the deity just sniffed at it, and said it stank. He then threw both eyeballs on the ground and crushed them with his foot. The arhat found to his dismay that compassion is not so simple. Not only had he failed to help the deity, but he lost both his eyes and received insults instead of thanks.

But the deity knew the limits of an arhat. "You cannot be expected to have a genuine Bodhi mind, so let me return your eyes to you." Thus even an arahat lacks the capacity for infinite compassion.

The deity said, "You should know that for innumerable lifetimes the Buddha has withstood what is impossible to withstand, suffered what is impossible to suffer, and given up what is impossible to give up."

We should learn to be compassionate. If we find genuine compassion difficult, we must remember that we are only ordinary sentient beings. At the very least we can practice not telling others to be compassionate, when we are not compassionate ourselves.

The third perspective is that of the Buddha. He perceives that all ordinary sentient beings are his equal; that is, that sentient beings, are really the same as the Tathagata. They are "thus come." In the Ch'an sect we say, "Every day we get up with the Buddha; at night, we sleep holding the Buddha." But since we do not have true wisdom, we remain ignorant that we arise and fall asleep with the Buddha.

The fourth perspective concerns the Buddha's teachings. Sentient beings vary according to background, situation, and disposition, so the Buddha varies his teachings accordingly. The Dharma is not and cannot be a fixed teaching; it is only genuine when it is flexible. When he expounded the Dharma, the Buddha taught what was appropriate to his audience. This is the true understanding of "reality is like this."

There is a story of a Buddhist householder who was a high official in the government. Someone told him of the Buddhadharma principle of "no-self, no other, no sentient beings," which is really a quote from the

Diamond Sutra. He perceived great truth in this.

One day he visited a nearby monastery in the mountains and questioned the master: "I've heard that Buddhadharma says there's nothing; no-self, no others, no sentient beings. What do you think of that?"

"You're wrong, there is a self; there are others; there are sentient beings."

The householder wasn't convinced: "Those are the words of the Diamond Sutra. How can what you said be true? Didn't you ever read the

Diamond Sutra?"

"I read the Diamond Sutra many years before you. It does speak of no-self, no others, no sentient beings; but that doesn't mean you can say that."

The official asked, "Why?"

"Do you have a wife and children?"

''Yes."

Then the master said, "Ask me whether I have children."

The official replied, "You're a monk. Of course, you don't have a wife or children."

"So for me it's correct to say no-self, no others, no sentient beings. As a householder, you have to say there is self; there are others; there are sentient beings."

The master adapted the teaching to the householder. Whether the teaching is of non-existence or existence does not matter, so long as it is appropriate to the particular sentient being. This is true teaching.

Now I will discuss the term, ''thus gone," which actually has the same meaning as "thus come."

The Diamond Sutra states that the Tathagata comes from nowhere and goes nowhere.

When the Buddha attained Buddhahood, nothing increased. When he was a sentient being, he was nothing less than he was at Buddhahood. Buddha Nature did not suddenly appear. Nor will it suddenly depart to leave "only" an ordinary sentient being. In essence, the Tathagata does not increase or decrease.

There was a well-known master in Taiwan who recently passed away. He was in his 90's when he died. His final words were, "Not coming, not going."

After he died, many Buddhists began repeating what he had said. It is true that repeating the words of a great master is useful, but since his words were directly quoted from the

Diamond Sutra, I couldn't be sure if they were simply a quote or really the product of great attainment. Some people were unhappy with this observation. "On the contrary," I said, "you should be quite pleased." After so many years of practice, this master ended his life quoting the

Diamond Sutra. He understood the words; not everyone is capable of that. Many repeat the

Diamond Sutra daily, but few appreciate the importance of what it says. Most people would not even think of the

Diamond Sutra when they are about to die. Their foremost concerns would be: "What is going to happen to my child? What is going to happen to my family?" It is a rare person who dies with the words of the

Diamond Sutra in his mind as this old master did.

The Madhyamika Shastra, the discourse on the middle view, states:

No entrance and no exit.

Entrance can have the meaning of arising or producing. Exit means departure, disappearance.

Most Buddhists are bent upon the termination of all vexations, the acquisition of wisdom, departure from existence, and ultimately, nirvana. These ideas are all connected to an entrance and an exit; they do not accord with the perception of a Tathagata.

Ch'an practitioners, like other Buddhists, seek to break through delusion and attain enlightenment.

The Platform Sutra says that within illusion, one is an ordinary sentient being; in enlightenment, one is a Buddha. Again, this idea of illusion and enlightenment belongs to the realm of coming and going.

It is not that The Platform Sutra is wrong. It is Ch'an practitioners who misunderstand the sutra. They conceive of a state called illusion and a different state called enlightenment. They wish to leave one behind for the other. This attitude leads to nothing but a rather bizarre state of mind.

Ordinary people who have no understanding of Buddhadharma suffer through many comings and goings: Today they make money, an increase. Tomorrow they lose money, a loss. Today someone gets married; one more in the family. A child is born, yet another. Perhaps a divorce lies in the future, someone departs. Parents pass away, more departure. All such comings and goings are common.

Truly understand "thus come, thus gone," and you will have much less vexation. There is really no gain or loss of money. Someone marries, but no one has really come. Divorce removes no one. In each situation it is "as if" someone has come, "as if" someone has gone.

I was once asked, "Does this idea of 'thus come, thus gone' mean that when I marry, I don't get a wife? When my wife gives birth, I don't really get a new baby? There's no one for me to take care of?"

That's not the case. The idea "thus come, thus gone" means "as if" they have come. You must take care of your wife as if you have a wife. Likewise, if you have children you have to take care of them as if they have come to you. Your wife and your children should not be the cause of your vexation. You have people in your family -- take care of them, but understand that they, too, are ''thus

come, thus gone."

Lao Tzu tells us to "act without possessing." This idea is appropriate to our discussion.

You must act responsibly in any given situation, but you must understand that you do not really possess or control anything. Otherwise, you are liable to get into trouble. Suppose your wife is particularly young and attractive. Others will be attracted to her. If you are possessive, you will suffer. On the other hand, you could rejoice in the attention given your wife. With an attitude of "thus come, thus gone," you will realize she remains your wife despite what others may do. And if she runs off with someone else? The same attitude applies: "thus

come, thus gone." It is as if she has come; as if she has gone.

A distinguished man I know in Taiwan had a wife about ten years younger than he. She spoke fluent English and had many non-Chinese friends. She ran off with an American and went to Hong Kong. Despite the outrage of his friends, he simply said, "The American gentleman happens to prefer the same woman that I do. He has excellent taste. I am quite pleased."

Six months later she came back and again his friends were upset: "How can you take her back after all that has happened?"

"I have a different point of view," he said. "My wife, too, has good taste: in comparing me with the other, she finally sees that I'm the better match. So she has come back."

Here is another story that happened in Taiwan. A Dharma master I know visited me during the New Year celebration. As was the custom, I presented him with an envelope containing a sizable amount of money.

He commented, "Between you and me there really should be no coming and no going."

I thought a moment and replied, "In that case, this will be the last year I give such a gift."

He said, "That's fine. In that case it will be as if it has come, as if it had gone."

His comment almost brought me enlightenment. What do you think?

Another line from the Diamond Sutra explains Tathagata further:

If you look at all phenomena and recognize that truly they are not phenomena, this is the same as seeing the Tathagata, the "thus come.''

If we want to see the Tathagata in ourselves as well as in other sentient beings, we must recognize that what we perceive as phenomena are not phenomena. Here, "phenomena" refers to self, others, sentient beings, and the span of life.

The phenomenon of the self refers to our own bodies and our own thoughts. This is the self. The phenomenon of others refers to the environment. This includes all living beings, all physical objects, and all events and occurrences.

If I can see myself and others, not as myself and others, then it is possible to see the Tathagata, the ''thus come." How can we do that? There are several methods.

The first method is analytical. To understand the idea of the self, we analyze the body and all that is related to it. This includes the mind and all of our ideas, knowledge, and experience. With careful analysis, we see that the idea of self is only a collection of physical objects and mental processes that seek to connect past, present and future experiences. We further analyze the components of these objects and processes, and we separate what we usually consider past, present, and future into discrete moments. We then ask, "where is the self?" It is not to be found. This is the analytic approach.

We can analyze our environment and recognize that all things are constantly changing. They are impermanent; they do not have fixed characteristics. Therefore, we cannot say that they have any real existence. Why, then, should we be vexed by illusion, by something that is unreal?

There are two additional categories of phenomena. The third is the phenomenon of sentient beings, really the sum of the phenomenon of self and the phenomenon of others. Finally, there is a category which is called lifespan which constitutes the continuum of time and space in which we live.

Truly see that there is no-self, and you will see through the phenomena of the environment, other sentient beings, and life-span. All four phenomena can be reduced to one phenomenon and that in itself is not real. See that all phenomena are not real, and then you will recognize "thus come, thus gone."

The first method is analytical; the second is the experience of practice. Reach the point where your mind is concentrated and unified, and eventually the whole mind disappears. "The mind disappears" means an end to self-centeredness. You begin self-centered, but when your mind is concentrated, you become aware of your self-centeredness. If you then completely let go, you depart from the domination of the self. This is the experience of "thus come, thus gone."

You may view Tathagata as a negative state, because the existence of all phenomena seen is to be denied. This might lead you to conclude that your wife is not your real wife, or that your husband is not your real husband. The same might apply to your children and parents alike. How would you be able to conduct your life? Obviously, the Tathagata state is not like that. No, at such a stage a person is free of vexations, not responsibilities. The Tathagata possesses great wisdom and great compassion. The Tathagata is energetic, altruistic, and filled with care and compassion for all sentient beings.

A disciple of Master Pai-Chang [720-814] once posed this question: "Master, you are busy every day from morning till night. What is the reason?"

The master replied, "Because I have no concerns of my own, I have no choice but to be busy."

From these lines I often express the idea that others have problems, but we simply have things to do. In this way we remain clear in helping others with their problems. This may be difficult to achieve at first, but at the very least we can realize that when we have vexations, others have them, too. In all cases when we strive to understand and live according to this attitude, we will grow more caring and compassionate.

All things in life provide the opportunity to practice. When we make money, it is "as if it has come, as

if it has gone." When we lose it, it is "as if it has come, as if it has gone." Good and bad things, too are "as if they have come, as if they have gone." We view all things "as if come, as if gone." This is the attitude of the Tathagata.

Achieve the attitude of the Tathagata, and you will have fewer mental obstructions. What physical obstructions you do encounter will cause you less suffering and vexation.

|

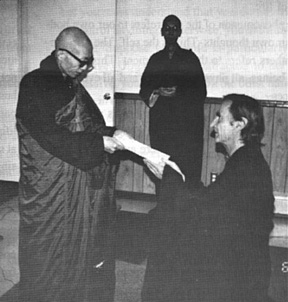

Master Sheng-yen presenting Dr. John Crook the

certificate of transmission. |

Chan Newsletter Table of Content

|